Head of Exterior Design

Felix Kilbertus’ take on design and Rolls-Royce

Felix Kilbertus’ take on design and Rolls-Royce

»The biggest challenge is to find an original path, an independent line in the truest sense of the word.«

Which visual experiences and impressions triggered your desire to become a designer?

I was a car enthusiast from the very beginning. I fondly remember a childseat up front between my parents so that I could see all the cars driving around us. My mother always tells me that I could differentiate cars before I could speak. I was certainly fascinated by the sculpture of cars, their surfaces and reflections, and the seemlingly ‘alive’ character that cars embody. There is something very human about their shape when you anthropomorphise them, but also something very animalistic.

It wasn’t until much later, when I was about 15 years old, that I realised that car design was an actual career and that you could follow an educational path. I saw this as a wonderful intersection of science and artistic aspirations, and so I followed that calling.

Where do you get inspiration for your profession today? Do you consciously allow inspirational impulses to have an unrestrained effect on you, or do you look for input from selected industries?

Both are the case and it’s the balance that counts. For me, there is a lot of power and impetus in fashion, architecture, art, film or theatre. Contemporary art and architecture are some of the most important sources of inspiration for me. Their aesthetic ideas, often quite abstract, can inspire our shapes yet do not overlap with car design in a direct sense.

The biggest challenge is to find an original path, an independent line in the truest sense of the word. That’s why it’s always important that the sources of inspiration are far enough away from your own field of work.

My old art teacher used to say: “As artists, we work for society – like everyone else.” Accordingly, I always see artists as part of an avant-garde tackling themes and problems intellectually, examining problems of values, including aesthetic values, sooner than others. A contemporary artist deals with things that will be relevant to everyone else in society only in later years.

That’s why I love to visit events like the Venice Biennale, the documenta or a good exhibition. Here I discover a sense of processing and distillation that I can utilise as a designer for certain topics, because I can identify some aspects of the future more easily through the perspective of art. Often, however, inspiration comes from all the small encounters, travels, conversations and the impressions that you experience along the way. It can be a small detail in a film where you suddenly get an interesting feeling and want to find out what is behind it and how it could manifest itself in the future in another shape.

Did you miss travelling as a source of inspiration during the pandemic?

Of course. The freedom to travel is a very important value and I missed being on the road immensely. Nevertheless, there were also positive aspects, because we were forced to slow down, rethink and review things and consciously classify them.

After all, before the pandemic, we were exposed to an inflation of stimuli and impressions, which was not always healthy and purposeful. Now, however, I am looking forward to travelling again, and also to meeting colleagues, attending events and motor shows.

»It’s about the serenity that the vehicle offers both in terms of acoustics and in terms of its design.«

You started at Rolls-Royce in 2017 as Head of Exterior Design. How much time was needed to really arrive there?

Before I started at Rolls-Royce, I set aside three months for extensive travelling. That was good preparation for facing the new task in a very open and fresh way. In the beginning, I decided to focus first and foremost on the founders’ spirit, the essence of the brand, the core values that this brand developed since its founding period. Rolls-Royce was, after all, a pioneering brand that has been pushing boundaries ever since.

I sometimes compare this with the spirit of Coco Chanel. Her modern vision shaped all future products, whether it was the famous “little black dress” or the first synthetic perfume. So, it was important for me to understand and permeate the Rolls-Royce spirit in order to judge input correctly and to help shape the products right from the start. A good start is crucial and I was lucky to find a very open-minded and young team right from the beginning.

By the way: how big is your team?

The brand design team is very small. If you add up all the important creative functions, Colour and Materials, Interior and Exterior Design Studio, the Bespoke Studio – there are about thirty of us. We are a closely knit team and exchange a lot on overarching decisions in order to create a common vision.

Do you make final design decisions alone, or do they often happen in the team?

In principle, I believe that in creative professions, even more than in other professions, you have to nurture ideas so that they can rise to the top and grow. The first rule for me is to support and back the team. Plus it’s about enabling them to take creative risks as well from time to time. My job is to cultivate a context in which creative excellence can emerge to move the brand forward, and I also specifically convey cultural principles to give the team direction and autonomy.

The further up the corporate hierarchy design topics are discussed and decisions have to be made, the more I am naturally called upon in my role as en editor. Finally, certain decisions are made directly, because as creative leaders we also have a responsibility to keep things clear.

In your position, you have to be good at anticipating what will be important in the future. Is this primarily an intuitive effort or purely a fact-based one?

First of all, it’s important to note that we know our customers extremely well, certainly a lot better than many other car brands do. We see what motivates them, as they are usually people with a very special strength of character and an extraordinary level of ambition and aspiration. In addition, there is a wealth of data, market intelligence and trend analysis available to guide us in the process. So we see how the perception of luxury is changing and how sustainability has been increasingly on our customers’ minds over recent years, for example. Additionally, there are all the technology-related topics like autonomous driving and other complex engineering issues we have to consider.

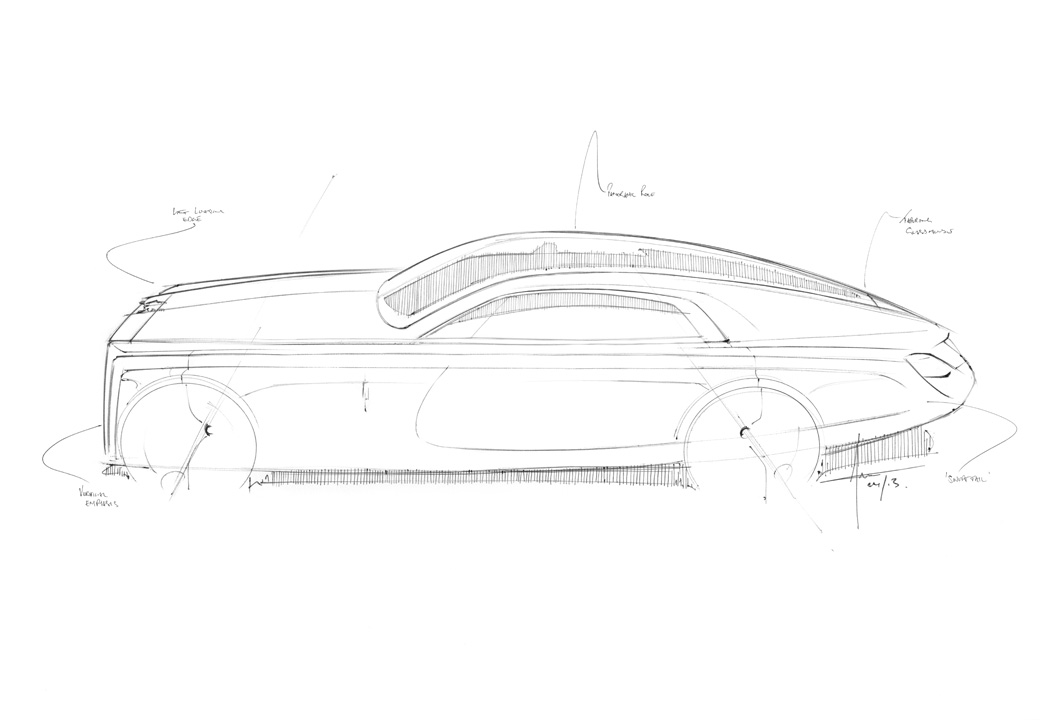

But ultimately, as designers, we are very intuitive people. This means that we have to translate all this information into design statements. For example, through the definition of certain lines, the visual sensation of lightness can be achieved. After all, we all interpret cars intuitively, and what we do as designers is shape the emotions that derive from the particular handling of surfaces, forms and proportions.

At the launch of the last iteration of the Ghost, the term ‘luxury for the post opulent age’ was used. What do you mean by this?

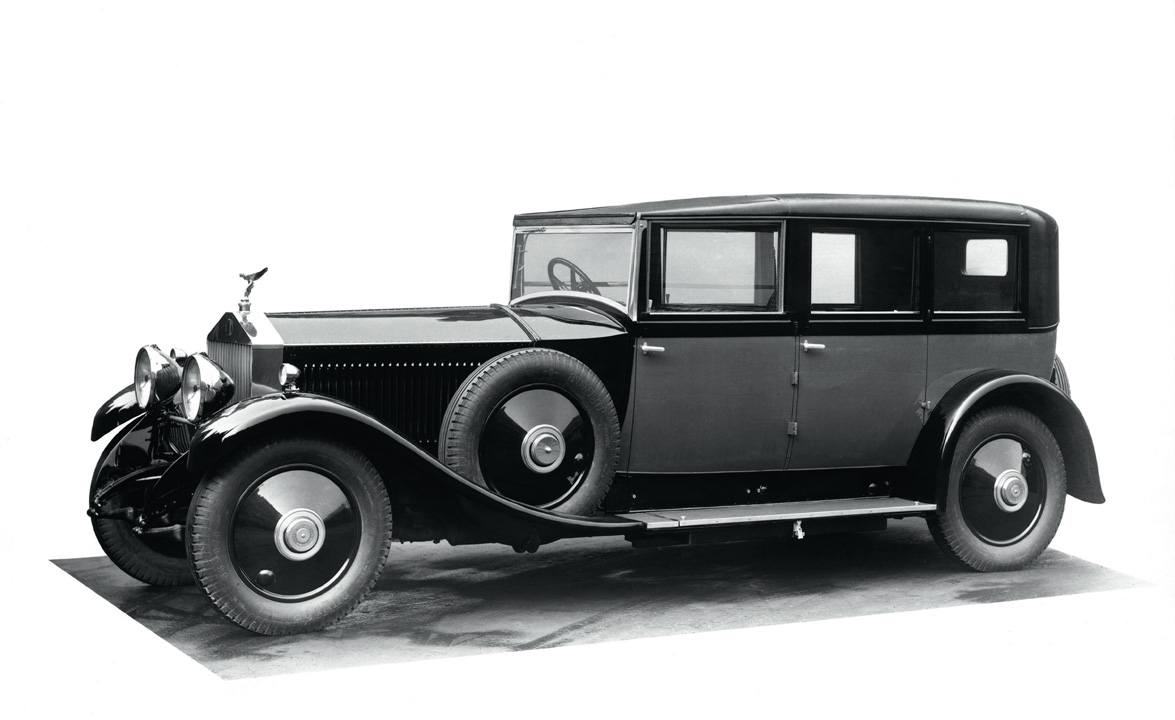

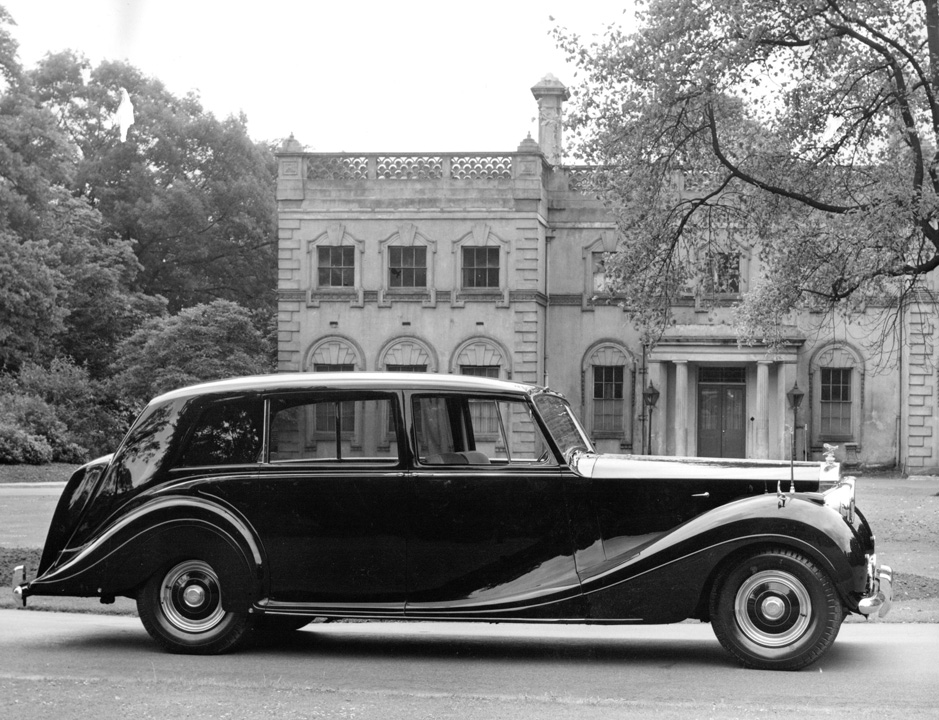

Let me tell you a short anecdote. I once attended a guided tour of a beautiful historic Rolls-Royce collection, mainly with cars from the 1910s and 1920s. After two hours of intense dialoge with the excellent host, we realised that the word ‘luxury’ had not been used once. It was all about reliability, quality, low vibration or individualisation. Luxury was and is merely the result of all these values and ingredients – but not a substance in itself.

That’s the difference between a superficial idea of luxury and brands like Rolls-Royce which focus on the highest possible level of excellence. ‘Post-opulence’ stands for the claim to consciously focus on the essence of quality in all aspects. It’s about authentic values and not about superficial symbols.

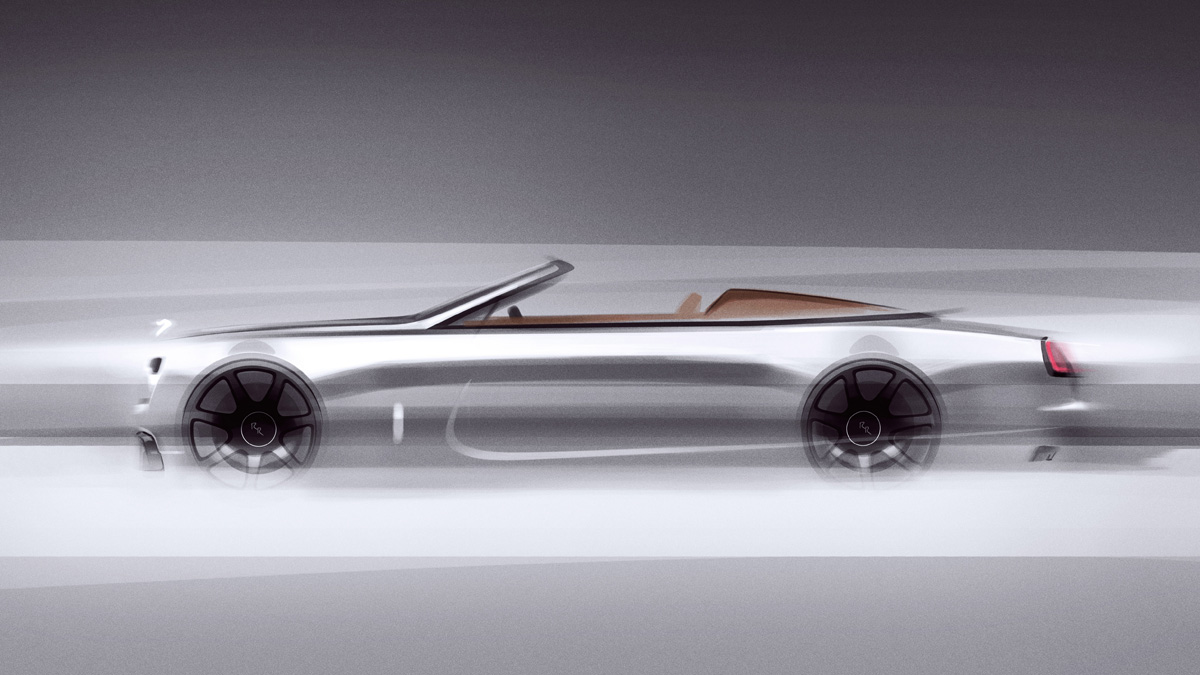

It’s about the serenity that the vehicle offers both in terms of acoustics and in terms of its design. It’s about souvereign lines without loud gestures. In exterior design, this is what we call ‘enchanting presence’. Very clear proportions and clean surfaces characterize this approach, which of course also applies to the interior.

The Phantom through time

Do you cultivate a culture of discontent in your team that, in a positive sense, allows the better to remain the enemy of the good?

I would say that permanent dissatisfaction with the status quo is a basic prerequisite for practising any design profession. Of course, there are those moments of questioning a design, when you need to revise decisions already taken in order to start anew, to reach the overarching goal.

The challenge is to find the right moment within these long development processes when this is possible and makes sense. At some point, however, you have to commit to an accuracy of a tenth of a millimetre, and at this level every surface transition, every joint dimension and every radius has to be frozen, and then there is no way back.

How much time passes between the first go-ahead of a development process and the final launch?

That clearly depends on the project, as you might imagine. A complete vehicle can take five years. Of course, there is also a lot of strategic preparatory work before such a go-ahead decision is even made. Then again, a minor model update can be completed a little bit faster.

Complex customised cars, such as the Coachbuild vehicles, take several years to develop. In the case of the Sweptail it was closer to six years and in the case of the Boat Tail at least four years from the initial idea to the final result.

Speaking of Boat Tail. Were you pleased that this design vision was so positively received worldwide?

Absolutely. The worldwide attention and appreciation we received for this very unique vision was very rewarding. It all started with the collaboration we established with a few selected customers and it turned into a beautiful and substantial statement of the Rolls-Royce approach to Coachbuilding.

Was there an experience or customer feedback in recent years that particularly pleased you?

What fascinates me about personal customer encounters is that the enthusiasm for the automobile completely transcends the most diverse cultural contexts or realities of life. There is a lot of passion for cars and their design in particular.

I met more than one of our customers – people who are incredibly successful in their professional field – but still tell me that they would have loved to become a car designer. This enthusiasm is a good reminder for us of what an extraordinarily privileged and wonderful job we actually have.

Thank you very much, Felix!

Join our Community