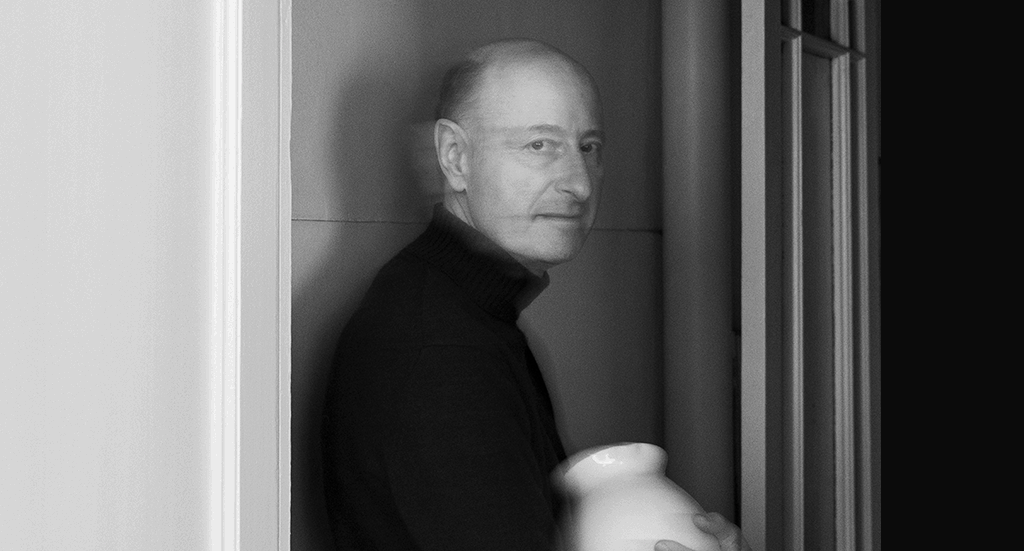

Thierry Genay

A master of light under Toulouse sky

Thierry Genay – Tranquillity and tension under Toulouse sky

»Many people feel a sense of calm in front of my photographs.«

What kind of visual environment did you grow up in, what shaped and impressed you during your childhood or adolescence?

I grew up in a small town in the south-west of France, very close to the countryside which I used to visit a lot. The family home was neat and tidy with a nice garden, my parents had a taste for arranging pretty things, objects and furniture from second-hand shops and antique shops. Music was very present, jazz, classical and more. In my youth I also acted in the theatre.

When did you discover the art world and which artists fascinated you?

During my teenage years I practised comic strips and I certainly had a taste for images, as my drawing teacher in high school gave me tailor-made subjects. But it was really when I entered the Beaux-arts that I discovered the plastic arts at the CAPC Museum of Modern Art in Bordeaux. Conceptual art, Land art, Minimal art, etc.

It was also in Bordeaux that the cinematic culture had a big impact on me. From that period, I would remember Richard Long, Lucio Fontana, Guiseppe Penone, Frank Stella… I was also discovering black and white film photography, but it was the composition that interested me, I had no precise references. It was mainly the cinema that educated me about images at that time. The image, its composition and its language.

Are Morandi or Chardin artists you can identify with – or are there others, perhaps?

Chardin remains a model for his exceptional sense of composition, for his approach to the essential, the further he advances in his work the broader these brushstrokes are, the more they suggest rather than describe. With Morandi, I like the use of a limited number of objects with which he worked over and over again. It’s not the object that counts, it’s the research and the exploration.

But in my pantheon, I would put Francis Bacon, always for the composition, for his harmonies of colours, for his inventive technique. Miquel Barcelo for his use of matter, his experiments. Pierre Bonnard for his composition and colour harmonies. Gerhard Richter for his synthetic vanities and his work with photography. Pieter de Hooch and Samuel van Hoogstraten. Vermeer for the light and the almost mathematical complexity of his compositions. I could also mention, in chronological order, Cézanne, Giorgio de Chirico, Gérard Garouste, Willem Claeszoon Heda…

In photography I would mention Irving Penn and in particular his series of still lifes for the Vogue magazine but he was a complete photographer. Roy DeCarava for his very strong and expressive compositions. And then Josef Koudelka, Josef Sudek, André Kertész, Outerbridge…

Had you already decided to go into photography during your studies at the Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux? Or did it happen later?

I went to art school to do interior design. I was also working for a decorator at the same time. Then I did my degree in clothing. Then I went to live and work in Paris in the field of fashion and textiles. As a graphic designer and then as a graphic designer and stylist. I worked a lot on trends. This is important because when you present trends you produce idea boards that are overloaded with information.

As a reaction to this work and to create more personal things I started to make clean graphic compositions from limited colour schemes and one or two graphic details taken from my trend boards. This was my first step towards still life. At the same time,

I was always interested in photography but mainly as a spectator until I bought a small compact camera and started to photograph my garden. Flowers, details, but there was a missing trigger to bring together graphics and photography… This element was a painting by Jan Jansz Van de Velde seen in Paris and seen again at his home in the Rijk Museum in Amsterdam. That was the trigger. I loved this off-centre composition, this large grey background that is almost a painting within a painting. The relationship to photography was obvious to me and still life was the best genre for precision work.

Why did you fell in love with this particular northern light?

I certainly owe it to Vermeer, Vilhelm Hammershøi or Pieter de Hooch. Like the painters I work facing the north near a window because the light is more constant there. This light expresses a certain calm, a reflective atmosphere and also a certain melancholy. It is an atmosphere conducive to the precise adjustment of backgrounds and objects to each other, and to lengthy experimentation.

Do you only use daylight without filters or do you create the light?

The northern light in Toulouse is not the same as in the Netherlands. It is more variable. Obviously, I prefer it on a rainy day than on a sunny one. So, I work with natural and variable light. I sometimes use a reflector to open up a part that seems too dark. I channel the height of the light, which allows me to play with the length of the shadows, which are an essential element in my compositions.

Speaking of Toulouse… are there any other regions or cities in Europe (or the world) that you love and that have shaped you?

For my artistic culture I would say Paris where I lived for a few years and where I still go. But I am also very sensitive to everything that can be discovered in Italy. Starting with the architectural beauty of the cities, with those facades that have broken with symmetry and which therefore remain an inexhaustible source of inspiration.

Do you work out the compositions before you shot or do they happen spontaneously while you are assembling them?

I rarely work on my compositions before starting a shoot. I prefer to choose a set of objects and backgrounds and start a research work. The object dictates a lot. If it is perishable like fruit and vegetables, I want to use it at the right time.

Sometimes I lend objects and I have a more or less limited time to use them. I also choose my range of colours, which is always limited. Then I consider the importance I give to the background, to the void in general. This choice determines the size of the final print, which can be up to one square metre.

»The start of a session is always a joyful moment.«

What is the most difficult and the most joyful aspect of your work?

Photography is a complex process, from the shooting to the final print. The start of a session is always a joyful moment. I shoot at home and develop at another location. I can be very enthusiastic when I shoot and disappointed by what I see on my development screen.

But the opposite is true, I sometimes “discover” the true value of a shot on the screen, not immediately but several weeks or even months later. And when the print is finally in front of my eyes it can be a moment of great satisfaction.

I suppose that 9 out of 10 people think, after a first look at your work, that they see a painting. How did your particular mix of genres come about?

I started photographing still lifes on an old marble fireplace with the wall as a background. Then I wanted other backgrounds, but I wanted to keep the material, so I decided to paint my backgrounds myself on canvas boards that I put behind my compositions.

Now these backgrounds also serve as a base, a support, which increases the pictorial aspect of my photographs. I like this ambiguity and it serves my work, which is inspired by painting anyway – but it came about naturally.

Your work reflects beauty as well as very intense moments of intimacy and spirituality. If you don’t mind my asking, what is it about you that is always reflected in your work?

It’s a natural question but it touches on something very personal. It’s difficult for me to answer it in words because if I could, I wouldn’t be doing photography. I would rather do art history or philosophy. That said, many people feel a sense of calm in front of my photographs.

Very few people rightly perceive a tension. One should not forget that a photograph is a snapshot but that, however, a research work cannot be quiet. So, my photographs express a double state. This is certainly part of the answer.

Your sensual use of fruit and vegetables suggests the following question: do you like to cook?

Yes, I like to cook. When I go to the market, I have a double look at the vegetables and fruits I choose. With me they have two lives. A life as a model and a life as an ingredient.

The link between the two must probably be the relationship with the material. A material that evolves (maturation) and that we transform (cooking). This is why the term “still life” is not appropriate. It is a very old misunderstanding.

Merci, Thierry!

Join our Community