One to watch

The Arash Rokni Interview

Arash Rokni on dealing with Beethoven, Bach and other challenges

»With Beethoven, it’s often like a confrontation with a mean giant. Sometimes you can stand him and sometimes you need distance. At least I do.«

Did you grow up in a house full of music?

In a household with an affinity for art, I would say. My mother is a painter, and the first records of classical music were all albums by my father, who was a great lover of Beethoven and Wagner.

How did you come to play the piano?

My mother had started learning a traditional Persian instrument as a hobby and accordingly regularly attended a music institute where she usually took me. Next to her in the classroom, there were piano lessons, and I was drawn to these sounds and wanted to hear what was happening.

Eventually, I just went in there once, listened, and I didn’t want to leave. That’s how it happened. At home, I started practicing on a small keyboard. And when things got a bit more serious after a few years, the first piano came to our house when I was seven years old.

It was love at first sight, so to speak?

Sure, it was. But it wasn’t necessarily the piano itself, but the music as a whole.

So, you started playing and practicing regularly at a young age?

Yes, but it developed naturally because fortunately I was never pushed by my parents. It was always my decision and that’s why it started with a lot of improvisation, just having fun at the piano and playing a lot of songs.

At that time, I wanted to be a film composer because I liked John Williams. It was only when I went to a music high school in Tehran at the age of 15 that I experienced piano playing on a very sophisticated level through my teacher, Tamara Dolidze, and then decided to do it full-time.

What happened next?

When I was 18, I went to Armenia and met a teacher there who was able to teach me the basics on a professional level for two years. That was for the first time really hard work. For example, he rented a hall, took me there, and gave me the task of learning works for a whole recital program within three weeks and performing them right there.

From scratch, really hard school. Through a classmate, I heard about study opportunities in Weimar, Leipzig, and Dresden, and so my path led me to Leipzig.

What gives you the greatest pleasure in playing the piano?

There are many aspects. It differs also from piece to piece and from concert to concert. Also, sometimes the social experience is a part of it as well. It can be very exciting in chamber music, for example. When you spend intense time with a group for a fortnight to practice and develop.

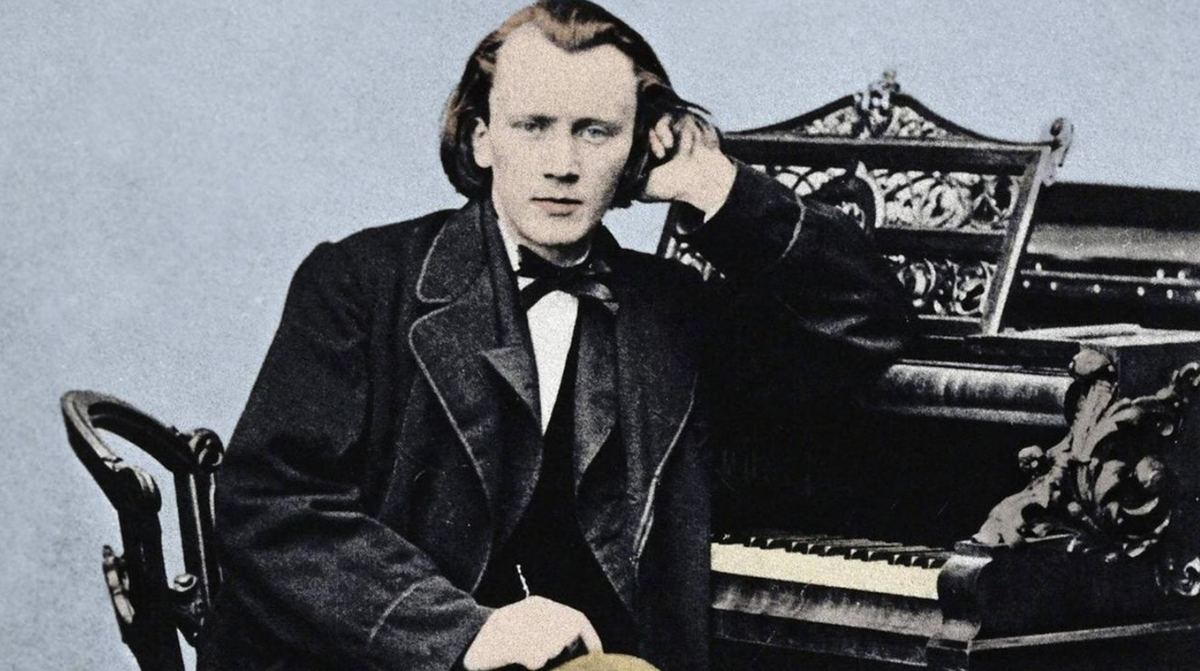

It’s also a bit of masochistic pleasure in it because after all, it’s also torture sometimes and part of the game. When you’re dealing with great composers like Bach, Beethoven, or Brahms, the study never ends. The supposedly perfect interpretation of a work may be even better tomorrow. But that is also part of the joy (smiles).

Does a thorough examination of a composer’s life help in the understanding of his works or is it sometimes rather the other way round?

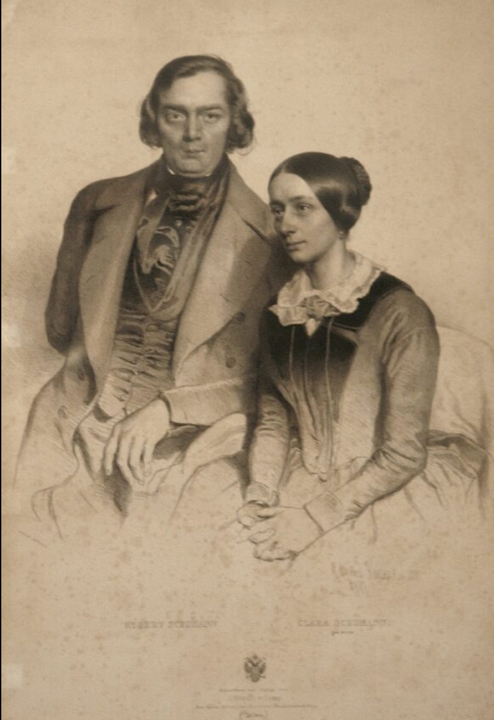

Both can happen. Robert Schuman, Is a good example. I think it’s good and necessary to do some focused research because he used many literary sources. Getting to know these works and understanding why he wrote exactly these Pieces helps a lot.

But sometimes it can also be very pleasant not to go into too much depth because then you sometimes come across a character who is not as interesting as you want him to be after all. That sometimes clouds the picture a little.

Is there also inner satisfaction when you play only for yourself?

Yes, definitely. But of course, there are phases, and not every work brings the same fun and joy. But that’s quite normal, I think.

Some musicians talk about a certain kind of flow that they play themselves into and perform at their best. In other words, a state that is like meditation. Is that the same for you?

Yes, but it honestly happens very rarely that you don’t have to think about anything at all and it really flows on its own. You become a receiver and a connector between music and ears of the audience and you are no longer important yourself. You rarely forget you’re playing a concert, because you’re being played by the music, so to speak.

Is that something you want to get into again and again once you’ve experienced it?

It’s incredibly beautiful at that moment because you really give everything. But still, there is a strange empty feeling afterwards. This emptiness is a tough experience, at least difficult for me to know how to repeat it again, to be honest, and you need time to come back to yourself. In this respect, the topic also has a certain ambivalence.

Bach, Brahms, and Beethoven, do you have a special relationship with any of the three?

Brahms and Bach are closer to me personally than Beethoven. With Beethoven, it’s often that he is showing to your face, that he is going to do exactly the opposite of what you expect him to do. It’s also like a confrontation with a mean giant sometimes. Sometimes you can stand him and sometimes you need distance. At least I do.

It almost sounds as if you enter into an imaginary relationship with the composer and a kind of inner dialogue takes place?

Yes, you build up your own relationship. But the image you have of this composer does not necessarily correspond to what or who he was. But if you have studied several works by a composer in-depth, then you could get an idea of what was probably going on in the composers’ compositional minds.

Do you also have a relationship with the traditional music of your home country?

I’ve been trying to get back into it for a few months now, also in terms of the musical theory that goes with it. There is something in traditional music in general that has been lost a bit in the so-called classical music, namely improvisation. This is even though improvisation was originally an integral part of Western classical music. Beethoven, Bach, Mozart, all of the famous composers we know could improvise. Also Brahms, Schumann, List and Chopin. All these composers improvised.

In those days, if you were not able to improvise in the best sense of the word, then you were not considered a fully-fledged musician. Nowadays, this claim hardly exists anymore, yet it is a really great opportunity for classical music. Otherwise, there is a danger that it will become a museum piece or a dead language which nobody is using, but everybody knows some phrases by heart.

Let’s go back to the traditional music of your home country. In the preliminary talk, you told me that it can take many years to learn just the basics. Why is that?

The leverage is in the didactics. In my home culture, teaching is done by listening. That may sound a bit primitive but it’s actually how music education should start and that makes it all the more intensely internalised. Reading and writing music is actually quite simple. True interaction and communication between an instrumentalist and a singer requires an ear and a memory that must be deeply internalised beyond theory like a language, and that takes a lot of time.

One has stuck to one’s self-composed basic framework, but taken the freedom to vary depending on the context?

Yes! There are examples, such as some Mozart piano concertos, where he didn’t write the figuration for the left hand at all because he filled it in one way or the other It was only when music was reproduced and published that the need for a more or less complete framework had to be met, of course.

Last November you recorded a new CD. When will it be released and how was the work in the studio?

The exact date is not yet known but the recording was very interesting and challenging. I recorded half of the CD in France on a newly built grand piano by the piano maker Stephen Paulello. The piano is called Opus 102, has 102 keys instead of 88, and is a whole lot longer. The resonance is correspondingly longer and much more transparent.

These extra notes in the bass and high ranges make it interesting and demanding. The other half is a total contrast. Here I play on a Blüthner grand piano from 1880. The idea of the album is to present music from the beginning of the 20th-century music on one half, Mossolow and Hindemith, and the other half with pieces by Brahms and Schumann looking at how these composers dealt with the Idea of expression.

Thank you, Arash!

Join our Community