Work hard, evolve smart

The stunning career of Passoni-Owner Cassina

Work hard, evolve smart – the career of Matteo Cassina

»I became a prisoner in a golden cage.«

Did you ever imagine, when you graduated from the University of Pavia in 1994, that your career would become so multi-faceted?

It’s like Steve Jobs stated in his famous Stanford speech: when you look back, there are a series of dots in your life invisibly connected to each other that actually defined this journey, so in the end, it all makes sense. I grew up in a village by Lake Como in a family where cycling was part of everyday culture. So, the best gift I ever received in those days was a tool box to assemble my bike. I spent hours and hours on it, happily focussed. When people asked me what I wanted to do for a living, the answer was clear:

I wanted to become a bike manufacturer. But time passed and I discovered my passion for rowing as well. That’s why I decided to go to the University of Pavia because they hosted Italy’s National Rowing Team and rowing training was part of the University programme.

My aim was to make it to the Olympics, but I fell short. Partly because I got injured and it took me a year to recover, and partly because I lacked that unconditional determination that you need to go all the way to the Olympics. By the time I was about to graduate from University, the legal situation allowed young Italians with a permanent job abroad to forego military service, so I decided to go to Latin America instead of following the pre-defined destiny of working at my father’s company back home.

What made you go to Latin America?

At the time, I felt that Latin America would become what Asia is now: an emerging economy. And secondly, part of my family emigrated to Argentina soon after WWII ended.

When I arrived there, I worked at Arthur Andersen’s most profitable international office because they managed all the privatisation of Latin America except for Brazil, which was an exceptional and mind-blowing context. It was all about sink or swim, and far beyond my comfort zone.

I turned from an introverted young man into someone who was able to build up relationships easily and I learned to work beyond my limits. But after some time, I figured out that there was no stable future in Latin America. This was during the Mexican Pesos Crisis which also affected Latin America brutally, so I decided to leave after two years.

Why did you choose London?

In 1995, when I was in Buenos Aires, I read the book ‚Being digital‘ by Nicholas Negroponte, who was an MIT professor and co-founder of the MIT Media Lab. This book talked about realistic future scenarios and opportunities in a digital future. It opened my mind.

I understood that this exciting future was about to happen very soon, and it made me want to work exactly at the intersection of future innovations and real business. So, the cutting edge financial players with units working on digital innovations where all based in New York, Hong Kong and London. And since London is only a two-hour flight away from Italy, I decided to move there.

At Goldman Sachs in London, you were introduced to the digitalisation of the financial services in its very early stages. You must have felt like an outsider in your industry for a while…

…. yes, you are right. The unit I worked in at Goldman Sachs developed computer systems that were able to trade electronically but that was not the most prestigious place to be, at that time. All the traditional traders, the kings of the world in that universe, treated us with very little respect. “Go sell your little software to someone else,” they said. A few years later everything changed, and they were out of a job.

Why did you go to Citadel after that?

Citadel was the only financial firm that disrupted Wall Street with mathematical models. It was the place to be in terms of the digitalisation of the financial markets. The magic happened there, with high-frequency trading and amazing mathematical and technological innovations that we were able to come up with. Twelve years after I started my journey in London,

I became President of Citadel Securities Europe. That was a business with a few hundred people, highly innovative and hyper-profitable. A crazy niche world of its own, totally focused but tough ride. Of course, you were paid well, but you had to give 100% all the time without any break in-between. I was lucky not to suffer a stroke, to be honest. So, the first thing I did when I left Citadel, was a six-month bike trip around the world with my wife and my son. We travelled 27 countries from June to February and it was a fantastic experience.

Is it true that the decision to invest in Passoni was made before you left Citadel?

In my banking career I became a prisoner in a golden cage. I earned good money, travelled the world and teamed up with really clever specialists but in the end, I just wanted to be free. Every sane mind knows that status and money don’t make you happy.

For me it was all about creating something on my own. I always had the dream of being an entrepreneur because it was part of my DNA and my upbringing. So, investing in Passoni and taking over full responsibility for the team and the brand was a milestone for me because I was able to experience real freedom.

But hold on, what about your time at Saxo Bank?

That was the last temptation that I could not resist because it was a totally different approach and another huge opportunity for me. Saxo Bank asked me to run their global business and I elevate myself to manage our global footprint in twenty-seven countries, legal entities and totally different cultures. I spent 250 days a year on a plane, I would wake up at 4am on Monday morning to go to the airport and came back at midnight on Friday. I often did nine countries in a week.

Many times, I had breakfast in Tokyo, lunch in Shanghai and dinner in Beijing. And again, what helped me cope with the pressure was maintaining the university lifestyle I had cultivated while rowing. Wake up very early, exercise and start work afterwards.

So, your ability to focus with that absolute intensity came originally from rowing?

I remember when I took part in a race, and after the very first minute you wanted to die because your muscles, your heart, everything was exploding… but the race lasts for another five minutes. That shaped me.

You invested in Zwift and you bought the very sophisticated, UK-based sports apparel brand Ashmei as well as Rouleur, the high-profile magazine for cycling culture – all that happened in 2016. How did you manage this in such a short period of time?

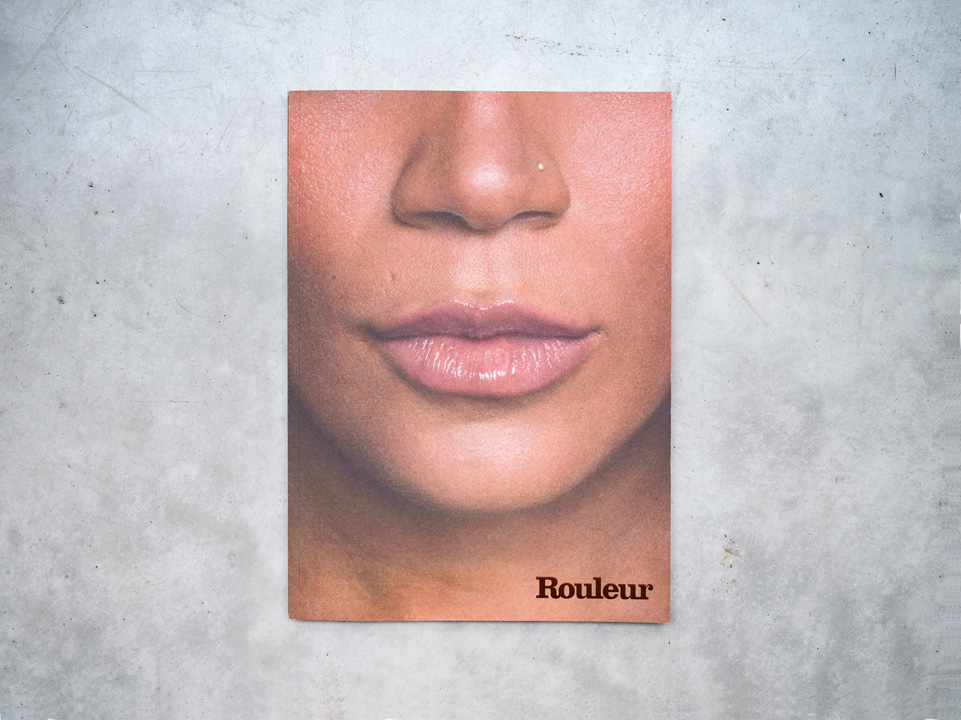

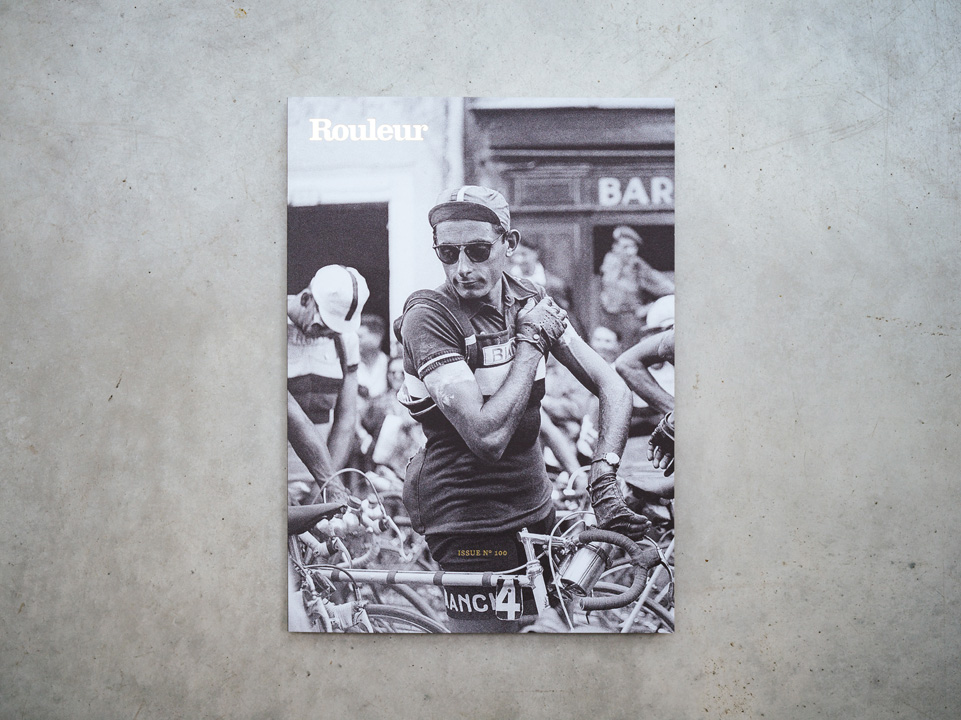

Let’s start with Rouleur. I’ve been a subscriber since the very first issue which was thirteen years ago. When I was at Saxo Bank, we sponsored a professional cycling team. That was the intersection where I met the editor of Rouleur and he told me straight away that they were looking for an investor. After I bought 100% of Rouleur and stepped in, I helped the team to change perspective. Firstly, that earning money is not a sin and that profit provides the freedom to deliver outstanding editorial quality. Secondly, I suggested to think bigger with different goals than before. For example, twelve months after I took over, we were able to triple the subscribers. Of course, the credit goes to the team.

I merely brought a new mindset into play. The third aspect is all about flexibility. For years and years the traditional print industry was profitable but as well very decadent because five people did the job of one. But today a journalist needs to have a very active social media profile of his own, he needs to know how to use a camera, how to update a website and so on. I am super proud that everyone rose to the challenge and so far, we have succeeded.

So suddenly you became a publisher. How does this feel?

I think owning a media company means that you have a lot of responsibility but also very exciting opportunities to set the agenda of important topics, whereas with Passoni I reach out to just a few customers a year without the same impact, of course.

Being a publisher is something I am super proud of. For example, when we published the Rouleur-Woman-Issue we featured the fact that a vagina can seriously be damaged by saddles and the industry doesn’t care at all. In the interview with the woman on the cover, a former BMX world champion, we talked to her about the downward spiral she faced that led to alcohol abuse, depression and many more tough experiences. Imagine this, Rouleur is a magazine about cycling culture but these topics are universally relevant, so we sold out three times in that month.

Tell us a little about Ashmei, please.

I met the founder, a very exceptional designer, at a Rouleur event and we started talking. I always loved the brand and for a number of years I’d been keen to develop a clothing line for Passoni with them. So after I bought Ashmei, the task was similar to the one I’d faced with Rouleur: combining a very good product with a very good team that could run this company profitably. Plus the magic question – how do you build a brand while selling products and vice versa.

Talking about ’how to sell’. Which are the biggest management challenges for you during the current Covid times?

For me, the number one concern is always and especially in times of crisis: cash flow. If you don’t have enough cash or the credit lines to stay afloat there is no future at all.

Borrowing money is cheap these days but the mechanisms within the markets have become bizarre: if you did very badly last year, the government gives you money. But if you did well, they won’t give you money, which is a bit stupid.

Coming back to your banking expertise: what are your predictions regarding the digitalisation of banking? Will the Covid crisis put a stop to traditional banking as we know it?

My thesis is that there are going to be a few newcomers and people that will disrupt certain aspects of banking, like PayPal for example. But a fin-tech in a Berlin warehouse with 20 developers will not disrupt global players like Deutsche Bank, who employ 40.000 people in tech units and spend nearly 20 billion Dollars a year on technology – it will never happen. The position of strength and the depth of services, relationships and competencies will preserve the traditional banks as solid players.

Final question, cross your heart: Are you a satisfied bank customer yourself?

When I call a bank in the UK these days, I stay on the line for three hours and it takes them three months to give me an answer, delivered by a call centre guy. In Italy, my family has been doing business with the small bank in our village for decades. If I called them this afternoon, they would give me loan on the phone because they know and trust me. So, cash is king and relationships are always the key.

Thank you very much, Matteo!

Join our Community