Vitra Design Museum

The History of (Female) Design rewritten

Here we are! – The History of (Female) Design rewritten

»We have started to look much more intensively at what and how has been collected, curated and presented in our house in the past.«

For you as curators, the question soon arose during the exhibition conception phase as to why so many women have been overlooked in the history of design to date. Of course, the answer lies in the patriarchal structures of our society that are still strongly rooted. Or is this too black and white?

As always with such social issues, the context is very complex and has to be looked at individually for all the women designers represented in the exhibition. We looked in particular at the situation of female designers to raise awareness that design history is also a narrative of the history of women in the world of work. In addition, we have a very specific collection at the Vitra Design Museum that focuses on furniture and interior design of the last 200 years, respectively since the beginning of industrial production.

It was important for us to focus on the social background. At the beginning of the exhibition, we present a historical review that first discusses the educational opportunities for women around 1900. In addition to the possibilities of an academic education, we also focus on the training opportunities in the crafts, for example as a carpenter. Was this possible at all? And if so, what difficulties were associated with it? Where were there female designers at all? Did they organise themselves and in which areas?

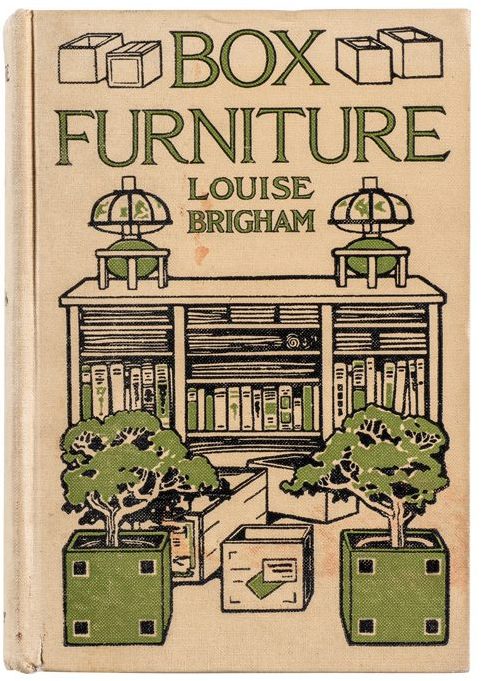

At the beginning of the last century, there were already female designers, but they were mostly pushed into fields of work that were assigned to women due to stereotypical role models, such as textiles or ceramics. In the male-dominated world of work, the view was often held that women were not capable of intellectual or even three-dimensional thinking. One of many prejudices that made it very difficult for women to enter design professions.

Does the exhibition therefore want to focus on the respective social contexts from 1900 until today?

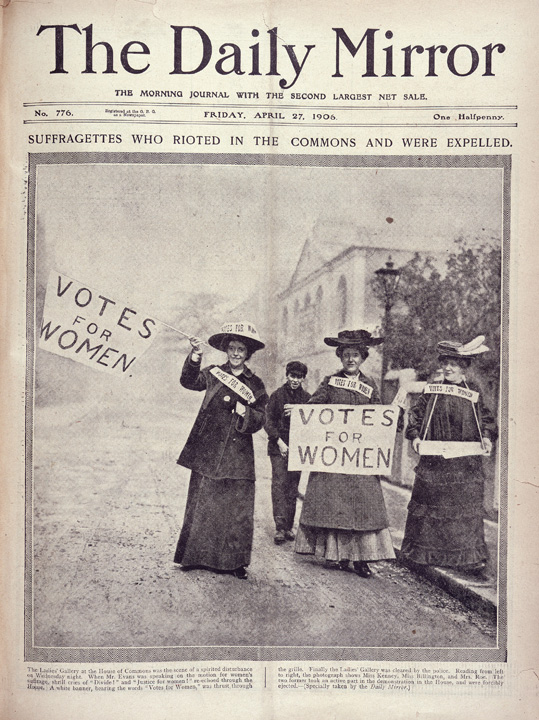

Exactly. The exhibition starts with a presentation of historical suffrage posters and shows the growing awareness of women to be able to change something in society through their own voice. Although there were already female designers who were able to practice their profession at the beginning of the 20th century, the educational opportunities were developed differently depending on the continent or country.

Scandinavia, for example, was relatively progressive and took a pioneering position in professional equality for both sexes. There, women were able to study and complete arts and crafts apprenticeships at a very early stage. In Germany, this development began to gain momentum in the environment of the Bauhaus School, founded in 1919, which for the first time deliberately wanted to treat women and men equally, at least according to the original curriculum.

But the development at the Bauhaus took a different direction …

Yes, you could say that. The initial proclamation of unrestricted equality was followed by a clear step backwards. Walter Gropius (ed.: Bauhaus founder and director at that time) feared that the reputation of his school would suffer if too many women enrolled. He systematically ensured that the number of female students was reduced, and the majority of the remaining women were shunted off to textile courses.

Which of the designers have started to fight against exclusion and how?

Here, too, there is an interesting example from the Bauhaus: Gunta Stölzl, who was the first female Bauhaus master and led the weaving workshop there. In contrast to her male colleagues, the magistrate of the city of Dessau wanted to pay her less salary, give her only a temporary employment contract and not recognise her professorial title. Under threat of dismissal, she opposed this decision and in this way at least fought for a more appropriate salary.

But the Bauhaus was no exception. Gertrud Kleinhempel, the first female professor in Prussia at the beginning of the 1920s, also had to struggle with this policy. By signing her employment contract as a professor, she had to agree to receive less salary and pension rights than her male colleagues. In addition, the employment contract prohibited her from getting married. Hard to believe nowadays, but unfortunately true. Nevertheless, she went along with it because she was determined to take this chance.

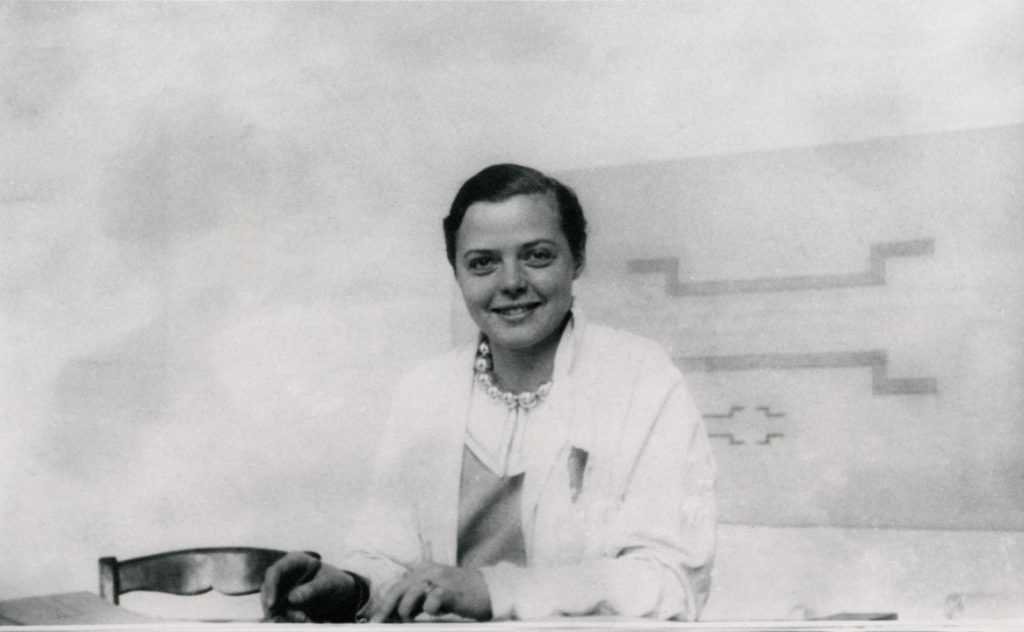

Let’s take the example of Charlotte Perriand. She worked in a trio with Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret and was largely responsible for the design of many pieces of Corbusier furniture. Yet she was never officially named. How did she deal with this?

Charlotte Perriand is certainly one of those women who, despite all adversity, went her own way with strong self-confidence and a good dose of pragmatism. Interviews with Perriand from the 1970s prove that she was ultimately able to deal with this situation quite confidently.

It seems to have been clear to her that the furniture would sell better in her time if only “Le Corbusier” was staged as a brand and maker. And finally, after some time, Perriand went her own, self-determined way. For example, she travelled to Japan at the invitation of the local Ministry of Economics and received a consultancy mandate there. Later, she worked with Jean Prouvé and his workshop, where her furniture designs were built under her own name.

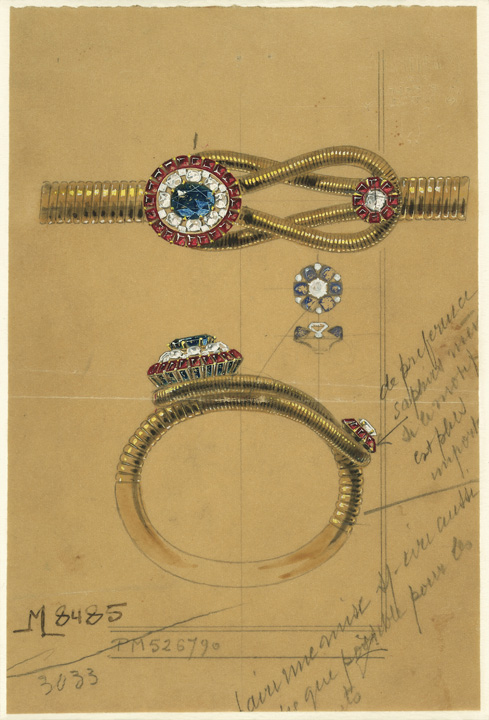

But other professional careers were also possible, as one sees in your exhibition. Jeanne Toussaint, for example, was appointed head of the luxury jewelry department at Cartier and Louis Cartier’s successor as artistic director in 1933. Does this strengthen the theory that the world of furniture design favoured particularly strong patriarchal structures compared to other industries?

It was certainly extremely difficult for women to gain a foothold in this industry. In contrast to jewelry design, furniture design was not attributed to women per se in the role model of that time. As woman designer, you needed a particularly strong will and a tough mind to prevail.

As one of the leading collections of furniture design, has the Vitra Design Museum contributed in the past to design history being told primarily as a story of white men? And is this exhibition therefore also a kind of caesura?

Absolutely, quite clearly. We have started to look much more intensively at what and how has been collected, curated and presented in our house in the past.

A change has already begun here with solo exhibitions on designers such as Daisy Ginsberg, Gae Aulenti or the artist duo BLESS, which now extends to the collection structure. We have changed our perspective, and that is certainly a kind of caesura.

In your research, were you able to prove that well-known design objects were falsely attributed to men when they were actually created by female designers?

We haven’t uncovered any entirely new stories, but we deliberately show examples like the Barcelona Daybed. To this day, this is mostly attributed to Mies van der Rohe, but current research knows that the design is actually by Lilly Reich. We can’t take credit for discovering it, but I think it’s also an important task of the exhibition to tell these stories again.

Flora Steiger-Crawford’s cantilever chair, which she designed in 1930, is another good example. This was originally attributed to her husband. Incidentally, this was due to the fact that women were not allowed to conclude contracts or apply for patents in 1930s Switzerland.

So, the exhibition is also intended to make the younger generations aware of the forms of structural discrimination that were practiced by politics and society even in recent history?

Yes. And of course, also that the concept of design as we know it is very narrowly related to classical modernism and industrial, serial design. Moreover, not only history but also historiography was strongly influenced by male-dominated points of view and classical role models until the last decades.

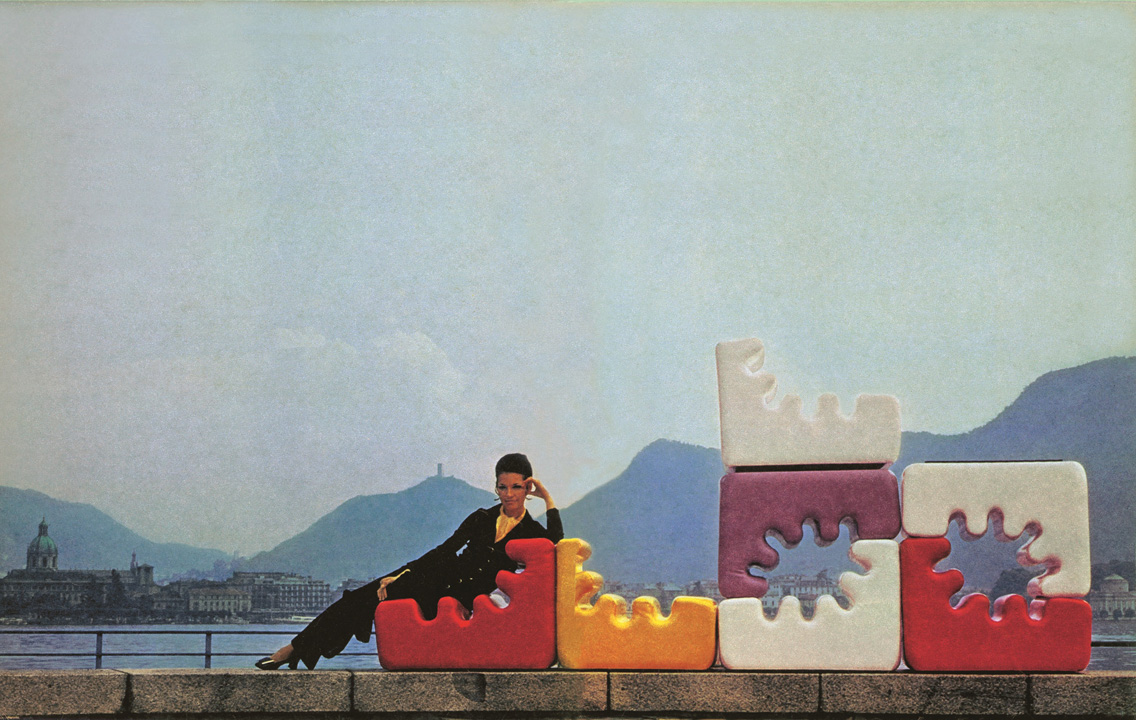

If you say goodbye to this very narrow narrative and simply look at what women designers have actually created in the most diverse disciplines, then the history of design becomes far more interesting and incredibly multifaceted.

Are there companies and manufactories that have promoted female designers and treated them as equals from the very beginning?

Here we come back to the already mentioned Gertrud Kleinhempel. Before her professorship, she worked as a furniture, jewelry and textile designer, for example, also for the Hellerau Werkstätten in Dresden. As a freelancer, she designed furniture for the Werkstätten, which was also produced and also featured her name in the catalogues. And she was not the only one there. About 50 women worked for the Hellerau Werkstätten in the first half of the 20th century. Likewise in the Wiener Werkstätten, female designers were able to successfully use their freedom there.

Your exhibition also presents objects by the US designer Florence Knoll, what makes her work so remarkable?

I find it remarkable that she was very successful as a designer as well as an entrepreneur in her own right. After the early death of her husband Hans Knoll, she continued to run the company for years. It is interesting that she got to know all the great names of classical modernism such as Mies van der Rohe or Marcel Breuer personally through her stepparents in her youth. She was almost certainly responsible for Mies van der Rohe’s designs being produced by Knoll. Florence Knoll promoted his career and helped him to become better known.

Today, almost half of design students are women, and women are leading the way in many groundbreaking design fields. Is the question of the sufficient visibility of women in design still relevant?

Of course, we as a museum are called upon to make our contribution so that women designers are not overlooked in the future. We have noticed that in recent years, for example at universities, there has been a more intensive examination of the topic. That is why the question arises why less than ten percent of professorships are usually awarded to women.

However, there are positive examples, such as ETH Zurich. In 2014, the university developed a Gender Action Plan and has been working intensively on the topic of equal opportunities and equal rights ever since.

But although the awareness is increasing, it still needs to be perceived and manifested more strongly. In practice, there is a lack of binding instructions on how to change things in the long term. Even if equal opportunities exist by law, in practice they often look quite different. Especially when women still have to fight to be able to continue their careers successfully as mothers.

Do you have a favourite piece within the exhibition that is particularly close to your heart?

There are, of course, hundreds of favourite pieces in the exhibition, as is always the case when you spend a year working intensively on these things. But what really made my heart beat higher is a carpet by Gunta Stölzl. Due to the pandemic, we had to limit our research to local archives and museums, so it was all the more incredible to discover such a key work for our exhibition in neighboring Basel. This carpet has rarely been shown in public before, which is why we can present this object in such great condition. It is a highlight, simply incredibly beautiful and a rare stroke of luck.

Furthermore, I am fascinated by the biography and the work of the Cuban-Mexican designer Clara Porset. She spent most of her life in Mexico designing objects that combined modern design principles with traditional elements of folk art. However, her thoughts on what a design education could look like in a new Cuban society are also fascinating. She discussed these with Che Guevara and Fidel Castro during her time in Cuba. There are so many multi-faceted stories to tell about this woman!

What is the next step for the exhibition?

Our exhibition, once it goes on international tour, will be a collaborative project. Our partner museums should consciously have the possibility to expand the exhibition if necessary. We know, for example, from our colleagues in Rotterdam that they will show contemporary, national women designers as a supplement in the context of the exhibition. This will always expand the contents of the exhibition, a gain in knowledge that we are very much looking forward to and are very excited about.

We have come full circle, because without the collaborative spirit of our trio of curators, Vivianne Stapmanns, Nina Steinmüller and me, our exhibition would not have become as wonderfully multifaceted as we can now present it.

Thank you very much, Susanne Graner!

(Ed.: The interview was conducted in German.)

Join our Community