21-30

Bowie’s favourite 100 Books – Part 3

David Bowie’s 100 favourite Books

Part Three 21-30

In Bluebeard’s Castle by George Steiner

“Four impressive lectures about the culture of recent times (from the French Revolution) and the conceivable culture of times to come. Mr. Steiner’s discussion of the break with the traditional literary past (Jewish, Christian, Greek, and Latin) is illuminating and attractively undogmatic. He writes as a man sharing ideas, and his original notions, though scarcely cheerful, have the bracing effect that first-rate thinking always has.” (Source: New Yorker)

Hawksmoor by Peter Ackroyd

‘There is no Light without Darknesse and no Substance without Shaddowe’, so proclaims Nicholas Dyer, assistant to Sir Christopher Wren and man with a commission to build seven London churches to stand as beacons of the enlightenment. But Dyer plans to conceal a dark secret at the heart of each church – to create a forbidding architecture that will survive for eternity. Two hundred and fifty years later, London detective Nicholas Hawksmoor is investigating a series of gruesome murders on the sites of certain eighteenth-century churches – crimes that make no sense to the modern mind … (Source: Goodreads.com)

The Divided Self by R. D. Laing

Laing sets of his theory of schizophrenia with the overall aim of explaining that psychosis is a reaction to an intolerable external world. He develops the concept of “ontological insecurity.” He describes this as an indefinable feeling of something lacking for an individual and a primary disturbance of the self. According to Laing, this ontological insecurity is at the root of schizophrenia. At the inner core of a person is their self.

The self is in the world and relates to the world by means of its body. Most people, most of the time, feel safe in their world. Laing refers to this as “primary ontological security.” However, for some individuals, this security becomes an ontological insecurity in that they feel persecuted by reality itself. An individual becomes concerned with preserving themselves. (Source: annaswartz.com)

The Stranger by Albert Camus

Published in 1942 by French author Albert Camus, The Stranger has long been considered a classic of twentieth-century literature. Le Monde ranks it as number one on its “100 Books of the Century” list.

Through this story of an ordinary man unwittingly drawn into a senseless murder on a sundrenched Algerian beach, Camus explores what he termed “the nakedness of man faced with the absurd.” (Source: Goodreads.com)

Infants Of the Spring by Wallace Thurman

It’s 1920s Harlem, and man, the joint is jumpin’. Folks are coming and going and everything’s copacetic as long as the gin keeps flowing. This is the scene Stephen Jorgenson dives into when he arrives from Canada for the first time. He is taken to “The Niggerati Manor, ” an apartment building in Harlem inhabited by aspiring artists whose true talents lie in living, and where everything’s black and white – with a lot of grayness in between.

Counterbalancing Stephen’s embrace of these folks is Raymond Taylor, a writer who is the only truly talented artist in the manor. Raymond’s cynical take on the “new Negro artist” is the tightrope he walks between the love and hatred of himself and his people. Characters representing Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Alain Locke all appear, and part of the fun of this book is figuring out who’s who. (Source: Goodreads.com)

The Quest For Christa T by Christa Wolf

The narrator and Christa T first met in school and again in university. She has a fairly conventional life – lovers, job as a teacher, marriage, children, an affair with her husband’s friend and, finally, the leukemia that led to her death. But what distinguishes her – at least from her fellow East Germans – is not only did she not want to participate in the East German way of life but she did not even want to be seen to be doing so. (…)

The novel made a huge impact in the West as it showed the alienation of East Germans from their society, but it should be read now as a novel about all of us. (Source: themodernnovel.org)

The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin

Why do we travel? It’s this question that haunts Bruce Chatwin’s classic account of a journey to the heart of Australia, The Songlines. It a a question in fact that haunted the celebrated English writer most of his life. Chatwin, who reinvented travel writing with his seminal book In Patigonia, was a restless soul. He travelled much of his life, which was sadly cut short in early middle age.

In the opening pages of The Songlines he offers one plausible origin for this inveterate wanderlust in a childhood spent constantly on the move. “I remember the fantastic homelessness of my first five years. My father was in the Navy, at sea. My mother and I would shuttle back and forth, on the railways of wartime England, on visits to family and friends.” (Source: travelmag.com)

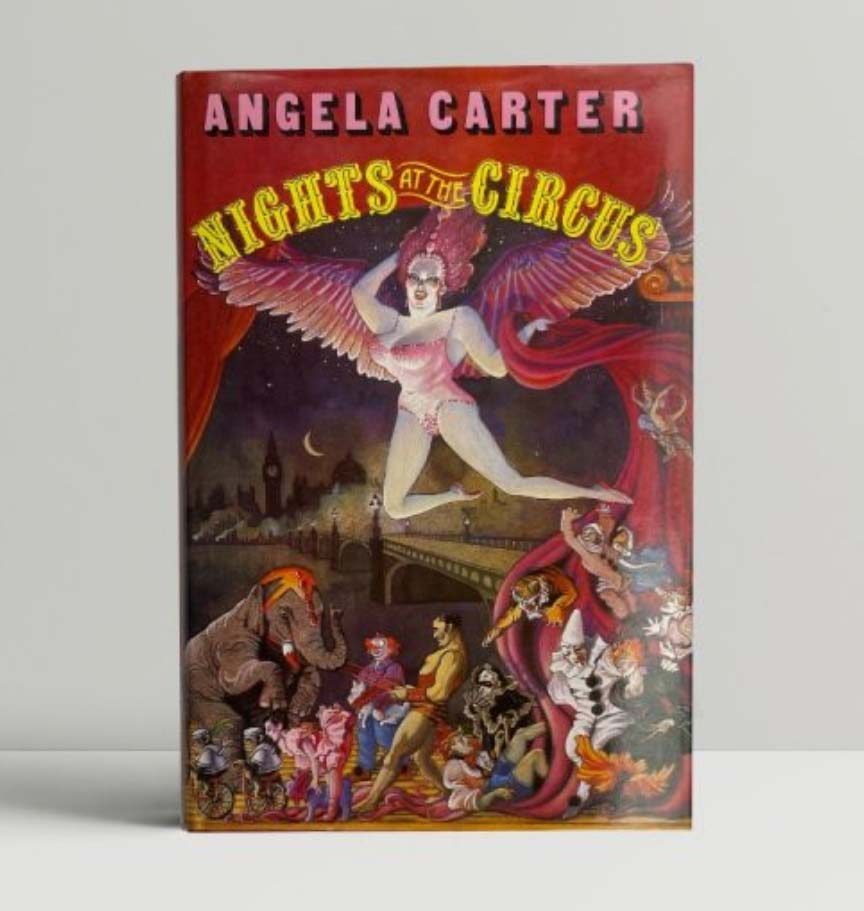

Nights At The Circus by Angela Carter

Courted by the Prince of Wales and painted by Toulouse-Lautrec, she is an aerialiste extraordinaire and star of Colonel Kearney’s circus. She is also part woman, part swan. Jack Walser, an American journalist, is on a quest to discover the truth behind her identity.

Dazzled by his love for her, and desperate for the scoop of a lifetime, Walser has no choice but to join the circus on its magical tour through turn-of-the-nineteenth-century London, St Petersburg and Siberia. (Source: Goodreads.com)

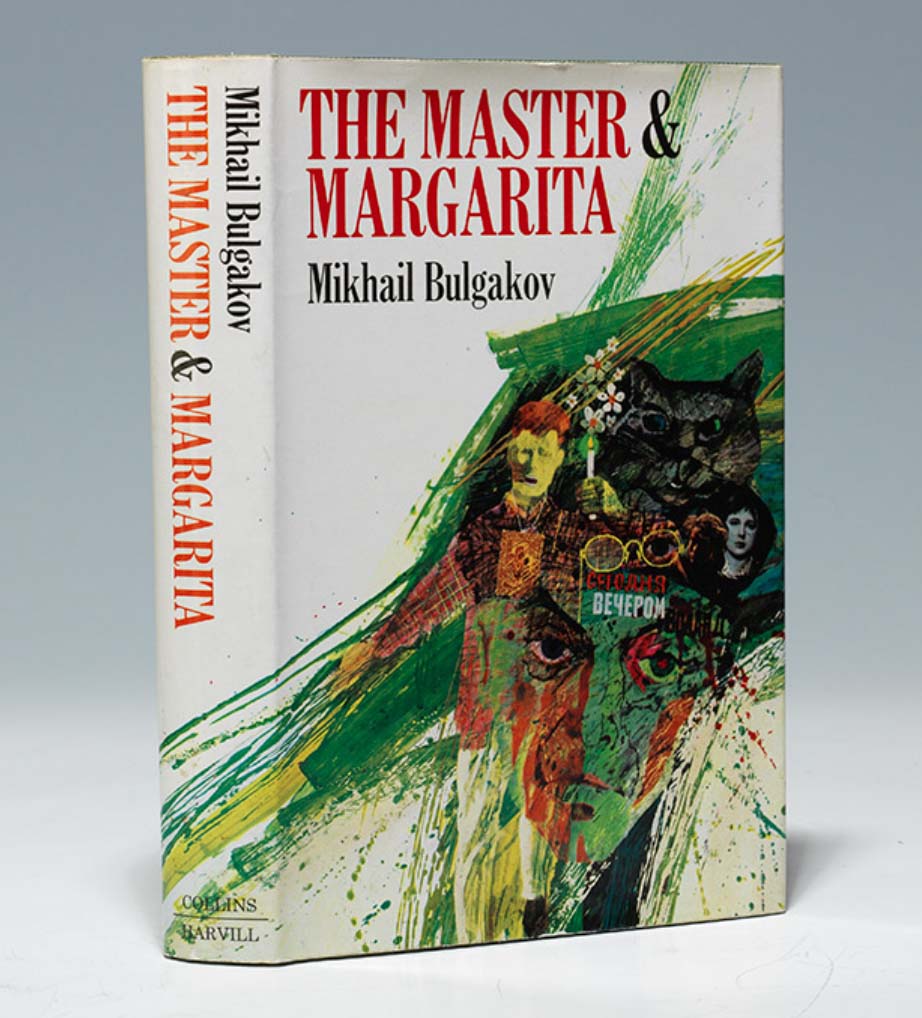

The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov

If many Russian classics are dark and deep and full of the horrors of the blackness of the human soul (or, indeed, are about the Gulag), then this is the one book to buck the trend. Of all the Russian classics, The Master and Margarita is undoubtedly the most cheering. It’s funny, it’s profound and it has to be read to be believed. (…)

Most of all, it is the book that saved me when I felt like I had wasted my life. It’s a novel that encourages you not to take yourself too seriously, no matter how bad things have got. The Master and Margarita is a reminder that, ultimately, everything is better if you can inject a note of silliness and of the absurd. (Source: Viv Groskop on lithub.com)

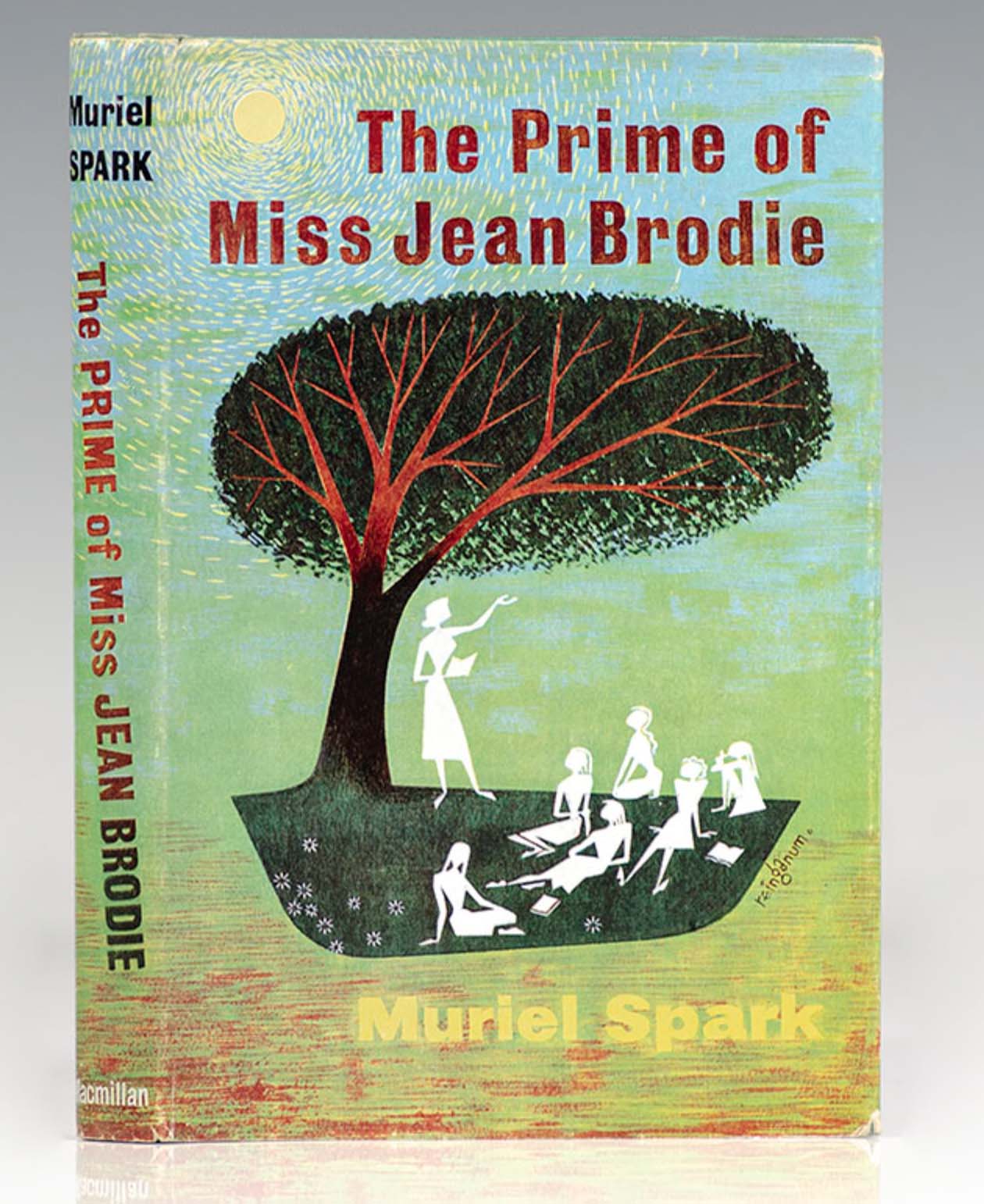

The Prime Of Miss Jean Brodie by Muriel Spark

I was amazed at the brilliance and complexity of Spark’s portrayal of an intelligent, passionate woman, robbed of her future by the death of her fiancé during WWI and instead becoming devoted to the cause of educating Edinburgh’s girls.

Miss Brodie is unconventional and daring; she gets the girls to hold up their textbooks in case another teacher peers into the classroom during their lessons; instead of teaching them what is inside its pages, she is telling them the story of her doomed fiancé, or of her latest European holiday, or of the rise of Mussolini in Italy. (…) (Source: Booksnob)

Join our Community