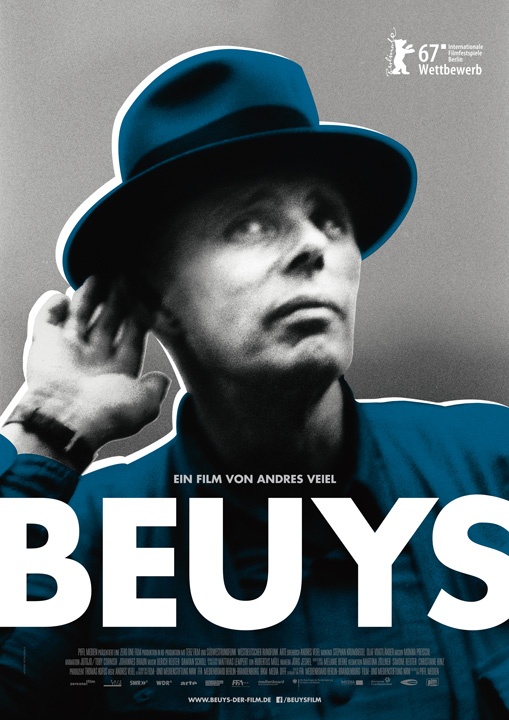

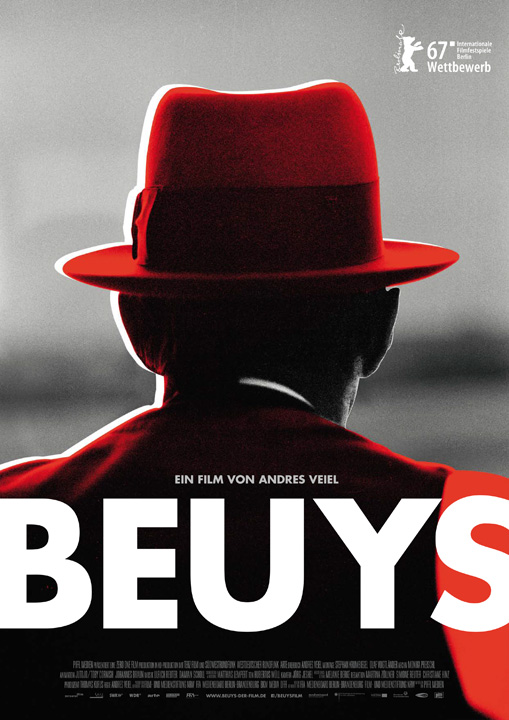

Beuys on film

Andres Veiel on Beuys’ gift

Andres Veiel on Joseph Beuys’ gift of Self Empowerment

»Beuys’ starting point was the concept of universal abilities.«

Before we come to your film and Joseph Beuys: What are you working on at the moment if I may ask?

My TV movie “Ecocide”, which was broadcast last November on Germany’s ARD public channel, continues to occupy me. Nevertheless, I have also started working on a completely different, new project: I am focusing on Leni Riefenstahl. In this context there are quite simply any number of important questions that relate to the present day. The question of seducibility, the question whether there can be anything right in the evil, or the question on Riefenstahl’s development and her role as a woman in the male-dominated world in which she lived and worked.

Nevertheless, to be honest, I had to think carefully about whether I would actually go for the project or not. But meanwhile I am completely convinced that it is right to look back at the 20th century to be in a position to better grasp the 21st century and our future. Incidentally, Beuys captured this perfectly when he said: “The causes lie in the future.”

Many thanks for your cinema documentary film BEUYS. As a person born in 1970 it was your film that first enabled me to understand what a great, free-thinking mind he was. No doubt you’ve often received such feedback on the film, I assume. In retrospect, how do you judge the general reception of the film now?

The film polarised opinion, like Beuys himself did. SPIEGEL magazine at the time ran a campaign to try and prevent the film winning the German Film Awards because they claimed it would ostensibly idealized Beuys and trivialised him. Retrospectively, I think that this is simply part and parcel of it all. In the film, Beuys himself says: “provocare” means to spawn something. Precisely in the case of this film I often found it very interesting and stimulating to encounter skepticism, opposition and rejection. Defense mechanisms trigger something in people, and that’s a good thing.

However, first and foremost the film succeeded in opening people’s minds. Creating an awareness of Joseph Beuys as a man of his times with all his vulnerabilities and also with all his humour, his casual side, his unideological approach. And an awareness of Beuys in the context of today’s issues. The film reaches those who want to tackle the basic issues of existence with an open, inquisitive mind, who are willing to be inspired. For me, it was one of the greatest premieres I have experienced to date. Both in Germany and on the international stage.

It seems to me that a very depressing moment in the film is the one in which Beuys finally didn’t succeed within the Green Party. Were the Greens the wrong party for Beuys or is it in your opinion completely wrong to wish to act in a party context if you are an artist?

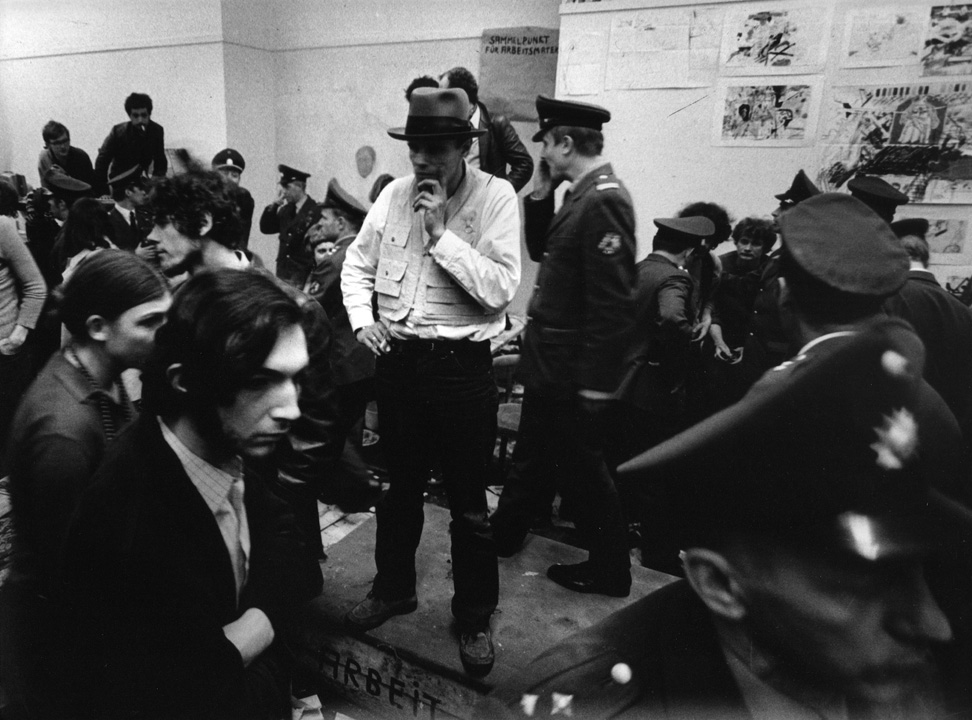

Beuys was initially very welcome by the Greens. Actually during their foundation phase he was, one could say, one of their inspiring key attractions. When the Greens after two or three years started to professionalize, fears arose that Beuys with all his ideas which at times were sometimes hard to comprehend would cost votes among the middle class.

Moreover, in their early days the Greens had extreme problems with especially high-profile and prominent individuals, as they contradicted the very idea of grassroots democracy. Taken together, this led to the massive rejection and that was a shock for Beuys. He simply could not imagine that people would not nominate him, would not vote for him in this party. Beuys was very skillful in organizing and selling his art, but he was no strategist who first created networks of power and that was why he failed in 1983.

In your film you show most poignantly that in the mid-1950s after an intense, personal caesura Beuys managed to find his way back into life. However, it was into a post-War society that clearly was in no sense prepared for a person such as Beuys. Do you also see it that way?

That was mutually determining. If you look at the crisis carefully, then it was without doubt also a post-traumatic response to World War 2 combined with a lack of success, great doubt, and most certainly immense loneliness. Yet he never stopped working and drawing the whole time. I always found it interesting that at the end of this crisis he came up with a piece he submitted for the competition for an Auschwitz memorial. For me that was a clear sign that during the crisis he must have intensively occupied himself with the question of responsibility and guilt. Later he was to make a very important statement in this regard: “I know I am guilty, but I reject guilt feelings.” This means that, borne as a representative of the generation of perpetrators, he of course knew of the guilt but most definitely did not want to get stuck in the paralysis of that feeling of guilt and therefore sought this way out by considering the idea of transcending guilt and in the final instance transcending his own failure.

What we must consider today is the fact that at the end of the 1950s there was hardly a single artist from the generation of the perpetrators who addressed the topic of Auschwitz and had attempted to address it in artistic terms. Back then, Beuys had fallen out of time and been abandoned by it in two ways: first of all by most of his friends with the exception of the Van der Grinten family and perhaps the one or other friend, and secondly in that solitary critical preoccupation with the Holocaust.

At the same time, one could view that crisis as an immense concentration of energy, don’t you think?

Yes, it is all about energy and about establishing a much stronger notion of healing through the use of specific materials in his art: Fat as the symbol of cold and rigidity, and conversely the introduction of the principle of warmth and movement in art. Making something mobile, giving it different shapes.

I believe that was the goal namely to overcome his own physical and psychological ossification and achieve a state of transcendence and healing. And on the basis of this experience also to recognize very clearly: It can’t be just about me, but it is also about an injury to society as a whole on which we all need to focus.

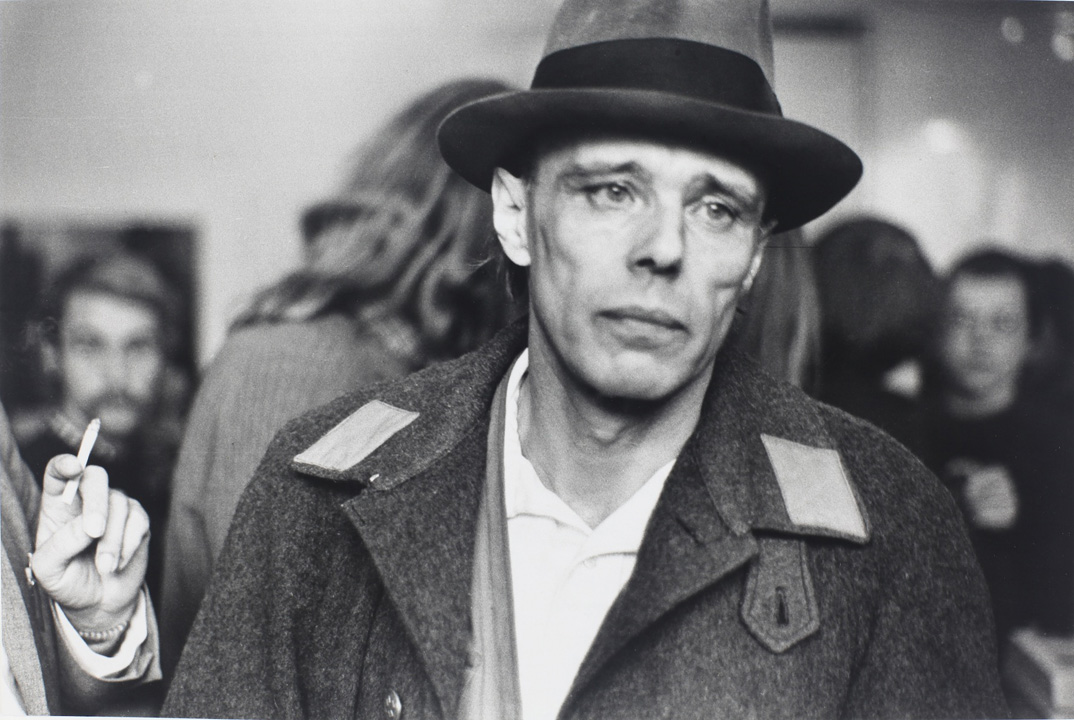

Beuys made a name for himself with his objects and actions. However, on second glance, it seems as if language was his real instrument. With a great talent to condense words and shift perspectives. Would you agree?

He was without doubt a master of provocation through abbreviation. He very deliberately not only factored in the misunderstandings when planning his work, but also provoked them. With almost all topics he addressed, he began by using abbreviation to great public effect, irritating and unsettling people. Only once you started concerning yourself with him over a longer period of time did you gradually start to find out what he meant.

The very sentence “Every person is an artist” has all too often been quite consciously misunderstood in order to sidestep any real engagement with the question: What powers to shape society does each and every one of us have and how do we use them? In the final instance, Beuys is someone who used language with utter precision. This can also be seen in the complicated titles of his works and drawings. He definitely chose these titles most deliberately or they simply occurred to him. There was nothing in between.

What aspect of his work do you personally find most interesting? Or is it the sum of all the parts that makes Beuys fascinating?

In Beuys’ case, at the end of the day the focus is always on three aspects that interact and make sense: His individual works, his biography, and the fact that he always highlighted and offered political-social ideas-spaces. To my mind, what is special about Beuys is that I can and must combine all three. In other words, from the art to his ideas-spaces and then on to his biography and from there back to the art. Which is to say, no field can be considered in isolation or conclusively. That’s what is great about him and why I continue to tussle with his output so intensively even after making the film.

In your film Beuys says: “The appearance of a new art in which all people cannot only participate but must participate. That’s what is involved.” In the same context he speaks of so-called “social art”. Where does this idea become most clearly manifest?

To my mind in his action with the 7,000 oaks. That is where he exited the museums and worked together with people. An art process that opens up spaces for people to experience, where people first perceive their own creative powers and can bring them to bear – and do not just go to vote once every four years. This is about self-empowerment. Beuys’ starting point was the concept of universal abilities and I find it trailblazing to this day. He does not start with the shortcomings but with what people are capable of and can contribute. Beuys was someone who repeatedly sought out precisely this momentum.

What especially sticks in my mind is that image when at the end the people who participated in the Oak action, both young and old, all start off with their watering cans in the middle of summer to water the trees. I think it’s a fantastic achievement. It’s this effect that I always striving for in my own work. It is a perspective that releases immense potential because it first of all creates mutual respect. And it’s also a way of seeing things that is painfully absent in society today and thus opens the gate wide for right-wing populists granting them access to people who primarily want to be seen and respected in the first place.

So whom did Beuys actually discuss his ideas with – who was his sparring partner? What was the role his wife played in this regard?

His wife was immensely important to him. She stayed at his side and in her own way held the family together while her husband was, as it were, on the road for years. Be it at the major international exhibitions and actions or owing to his work for the Greens. He had an incredible amount of creative energy for his actual artistic work and needed neither companions nor sparring partners with a view to a critical review or revisions.

However, he did constantly interact with people, often until well into the night, irrespective of with whom he was talking. There’s the famous anecdote of a discussion [at an event] with two brothers who were on day release from a psychiatric ward and told him this and their high esteem for him. Whereupon Beuys laughed and responded: “Well, then at least there are now three of us.” Beuys certainly never selected whom he talked to in terms of furthering his career, he wasn’t interested in that sort of networking. He had gallerists to do that and made sure they did.

Let’s turn to the international impact: In what countries did you get the most intensive feedback on your film?

You would be better off asking Rhea Thönges-Stringaris, as I was only along for some of the trips, and she presented the film at over 20 film festivals. I can say a lot about the USA, the two screenings in Paris with a lot of debate and responses, about London, Switzerland, Austria, and also Italy… You see, Beuys really made a mark and to this day there are people who remember those days and approached me after the screenings.

To my mind, what is far more important than walking down memory lane is the question: Who of the younger generation recognizes that he provides questions and answers to the challenges of the 21st century? That is actually the main objective, that the topics and issues get taken up and moved forwards and that Beuys gets read and discovered anew. If the film achieves that then the five years of work on this film will have been worthwhile.

Are there any next-generation artists where you feel Beuys’ heritage is being absorbed or held high?

I wouldn’t want to explicitly go for one name. For me, it isn’t significant whether someone refers to Beuys; what counts is that the basic questions on the potential of art are constantly rediscovered and renegotiated. The experience of recent years has shown that there is a strong need to participate in formulating these ideas and to reflect them in one’s own actions. The issue is to think the possibilities, to realise ideas and to crack open social conditions that have become frozen solid.

Given that 2021 is Beuys Year there are reasons for worrying that the media will celebrate the artist extensively but the ideas that spurred him on, that he helped forge, will all too often get ignored. What do you think?

I would rather see that in the reception Beuys is still very much a cause for overall concern. However, a real engagement with him presumes that one is truly worried by the state of the world, feels the pain, and derives from this the necessity of change. Anyone who doesn’t or can’t see this will always find Beuys threatening and with him the themes he highlighted. Beuys, or so it would seem, tends to be seen in the media more as that 20th-century monolith with whom most of the editors do not really want to engage. Beuys is troubling.

What is great consolation is that the debate of the art critics in the media is a far cry from how people responded directly to the film, showing how open they were for new debates on him and his topics. Or, firmly in keeping with the Beuys action “Marcel Duchamp’s Silence is Over-Rated”, I would say: The mumblings of the art critics should not be over-rated.

Thank you very much, Andres Veiel!

Join our Community