The Johann Scheerer Interview

Music, errors and analog attitudes

A conversation about music, errors and analog attitudes

»My work is definitely about the love of the unexpected and creative error, which is usually anything but.«

Did you grow up in a household full of music?

Far from it. My father listened to Eric Clapton, Cream or Led Zeppelin every now and again … like once every five years or so (smiles).

At some point I came across the Austrian composer, singer and poet Georg Kreisler and through listening to him I also discovered other German lyricists.

This developed further with German bands like ‘Die Prinzen’ or ‘Die Ärzte’ and then I moved on to the English cosmos. So basically, I have brought music into my life all by myself.

What music did you personally discover that first catapulted you into another universe?

It was the German Band ‘Die Ärzte’ and, above all, their singer Farin Urlaub with his “I hate everyone” attitude. That resonated perfectly with my teenage self. For me, the cliché of the young man with his guitar protesting against something and standing his ground was quite compelling. In retrospect, quite macho-like, but it just fit at that time.

Plus, it was paired with a wonderfully confident self-irony. To be extremely sure of oneself while not taking yourself too seriously – it doesn’t get any better than that, and of course, ‘Die Ärzte’ conveyed this perfectly.

So, the first record you bought with your own pocket money was also by ‘Die Ärzte’?

Yes, I think it was the album “Die Bestie in Menschengestalt” (The Beast in Human Form) in the early 90s, which I bought at my favourite record shop WOM in Hamburg. A really huge record superstore, like Amoeba Music in LA or HMV at Picadilly Circus with a stunning selection. I loved shops like that, where I could spend hours and always discover something great.

When and how did the music cosmos open up to you in its entirety?

I started playing in a band very early, at the age of 13, and we made a record in a DIY studio. At that time I didn’t know anything about anything, not even about my own instrument. But we somehow managed to do it and then we became more professional relatively quickly. We won a band competition, got a professional record contract with Sony and yet the whole project didn’t work out that well.

It wasn’t until I started recording stuff for myself, quite low-key, that it felt like this is what it had always been about. I realised that I never wanted to do anything else apart from recording ever again. A stroke of luck!

That’s enviable!

True, but to be honest, it took me some time to understand that you can’t take this stroke of fate for granted.

You got your first guitar when you were 13. Why the guitar?

Well, the question is, what else is there? The guitarist is at the front and sings, so the guitar is the go-to instrument if you crave a certain amount of attention (smiles).

How long has Clouds Hill Studios been around and why the name?

Clouds Hill Studios started 17 years ago, and the name is a tribute to Lawrence of Arabia’s retreat in Dorset in England. It’s a small white cottage that I had seen on photos at the time and was fascinated by. And I was fascinated by the man himself.

I was inspired by the idea of this retreat, secluded in a safe place with cozy furnishings. Just perfect for people who lead an adventurous life out there as super-agents or musicians, but who also need retreats like this to be able to concentrate on what it’s really all about.

Did you experience this in other studios as a musician, or was it exactly this missing aspect that shaped the origins of Clouds Hill Studios?

I really missed this in most of the studios I got to know. Most of the time the studio atmosphere was characterised exclusively by music clichés, full of golden records and thick leather armchairs – too one-dimensional and uninspiring for me. People usually don’t write their songs in a recording studio, but at home.

In the transition to the all too hyper-professional environment of a traditional music studio, however, something usually gets lost and that’s what we want to prevent. The atmosphere in our studios deliberately builds a bridge and creates an almost intimate place where creativity is all that matters, regardless of the art form.

Clouds Hill is an analog studio. What are the main differences between analog and digital recording?

The differences are technical and emotional, I would say. The best possible method of recording music is still analog. Because just as we communicate with each other right now in analog form and sound waves from my vocal cords and my tongue make something resonate in your ear in all its infinite facets, analog recording technology ultimately works in exactly the same way.

From the membrane of the microphone to the pressing of the records. With digital music recording, a decision has to be made at some point in the process as to whether the input is a 1 or a 0, and logically something is lost here. You don’t have to make that decision in analog.

But can you really still hear the difference in terms of quality nowadays?

Of course, this is on a very subtle, meanwhile hardly audible level … but that is where the emotional or process aspect comes in. In the digital context, you can record as many takes as you like, but an analog tape has limited space.

This requires making certain creative decisions in advance and my experience, this is usually a very good thing. In addition, analog recording requires an interplay of many individual skills of different players and this very context usually creates an added value that a one-man digital studio simply cannot offer.

An analog studio makes sense when maximum competence is always at hand. It’s about emotional intelligence, turning little errors into unexpected and wonderful benefits. This is what analog recording is all about at the end of the day. When you’re sitting at a computer, unexpected things don’t usually happen.

Speaking of errors. Are there artists who need your guidance to appreciate the power of the unexpected?

That happens all the time and it’s in fact the core competence of the music producer: to know when something is finished and to recognise whether certain mistakes are simply not mistakes at all. Because musicians usually don’t know that. My work is definitely about the love of the unexpected and creative error, which is usually anything but.

Does your role as a producer automatically adapt to each artist?

Of course, there is a certain coherence in the way I work. But every musician is different, and you have to adapt to that. Fortunately, I only work with artists I really like and whose work I appreciate. It doesn’t matter whether they are famous or newcomers.

Sometimes there are more experienced artists who already know exactly what they want and are just happy that I’m simply at hand with my experience. Knowing when to consciously give no input is also a necessary skill of a good producer, I’d say.

… and do you often bring in therapeutic skills?

95% of my work is exactly that (smiles).

You also work very closely with Omar Alfredo Rodriguez-Lopez. A guitarist who has been internationally successful with bands like The Mars Volta or At-the-Drive-in. How did this come about?

We were introduced by a mutual friend and went straight into the studio to record something, that was in 2006. The intense level we are at now is the result of 15 years of getting to know each other. It takes a long time to gain the trust of successful artists. Especially given that unfortunately, there are far too many idiots in this industry.

You are talking about record companies?

Basically about the entire music industry. There are just an insane number of completely incompetent people working there, it’s really grotesque. That’s why more and more artists have joined us over time, because they realise that at Clouds Hill we are into music for the sake of it.

Take James Johnston from Gallon Drunk, for example. He was once asked in an interview why he would record with a young guy in Hamburg of all places and his answer was: because he gives a fuck. Sounds strange, doesn’t it? Actually, one would think that passion for music should be a given in the music business. But to this day it is not, unfortunately.

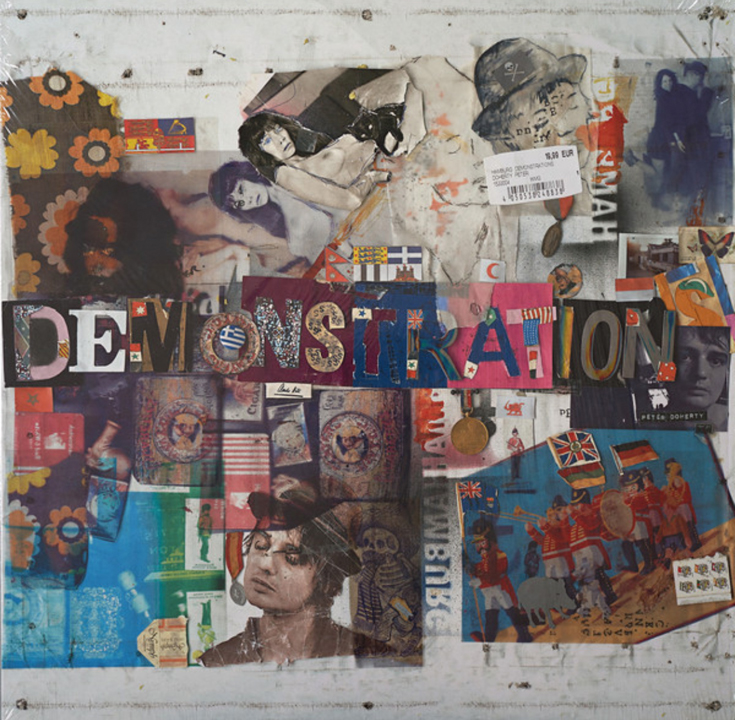

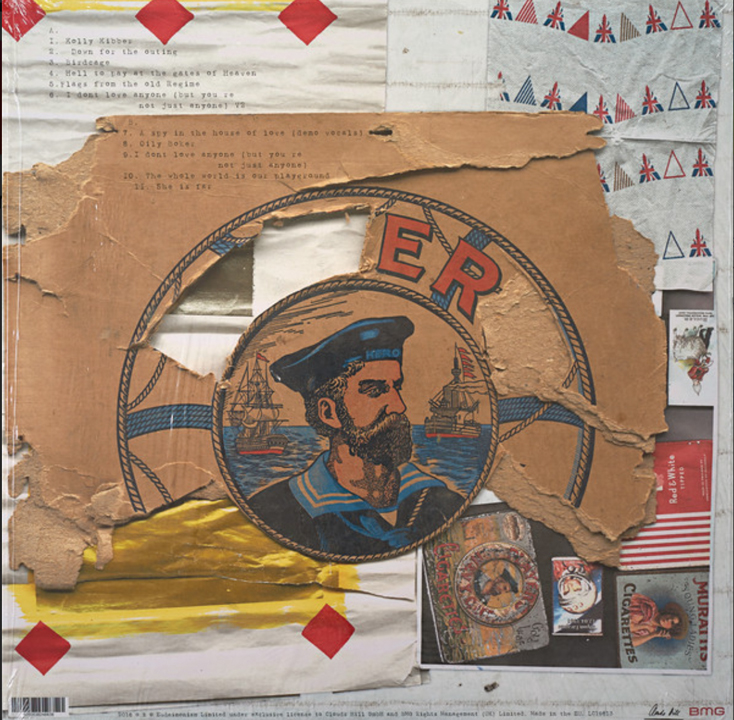

Please tell us about the collaboration with Pete Doherty and the album ‘Hamburg Demonstrations’.

After a first short visit to our studio, I received a text message from him asking me to produce his next solo album. I asked him why he wanted to do it and he referred to the intimate and interdisciplinary atmosphere that we have created here, and which makes it possible to set authentic moments to music.

In the end, the album took three years of intensive work, but it was worth it. In any case, it’s one of the three albums that could be on my tombstone one day. Some of the musicians who worked on it told me that they had never listened to the album because they had such an intense experience and simply didn’t want to revisit that.

In theory, you usually come in as a producer when the song is already written. Do you still get asked to get involved with any songwriting?

Yes, sometimes. But my perception of my job as a producer is actually that I want to work with someone who is able to write everything on their own. I have no interest at all in working with pure performers. I am interested in taking all that is at the core of an artist and refining it with them so that it touches people. That’s what it is about.

Since 2009, there has also been a record label in the Clouds Hill context. Why is there still a need for a record company these days?

At the end of the day, no one needs a record company, and the industry has really done everything in the last few decades to abolish itself. Full stop. Of course, a band like The Mars Volta can go to any label in the world, ask for the money they want, and deliver a record. And of course, such a band can also set up a label themselves and remain successful.

What ultimately makes the difference is the demand of such sophisticated artists, who appreciate getting input and support from a team that works with the same mindset and the same quality standards as they do.

Labels are not obsolete when they offer more than the usual label work. A second home like this place and a team to fall back on at any time. That’s it. A mixture between management, part-time-parents, best friends and business partner.

And what’s the story behind the ‘Volta Cube’?

As with every new album launch, we asked ourselves what we needed to attract not only fans but also new listeners to the band. For us it was clear that it couldn’t be ‘just another’ digital campaign. The Mars Volta are a very real and tactile band, so it was about offering an equally tangible marketing experience.

And then we identified a designer and architect from Venezuela who was a big fan of the band and had attracted attention through his fan art on Insta. With him, we designed the Volta Cube, following the vision of Omar Rodríguez-López.

A black cube that was set up in Grand Park in Los Angeles 48 hours before the single was released. But only those who were actually prepared to go into the cube for three minutes to experience the light and sound installation and listen to the single got to hear and see everything.

And the feedback?

… was overwhelming. One fan, for example, flew in especially from the Philippines to experience the Cube. He took Omar’s signature guitar with him to take a photo in front of it.

We had about seven hundred people pass through in 48 hours and had a 300-metre queue in front of it the whole time in the middle of downtown Los Angeles. It also created a lot of buzz on the internet and PR for the album that we wouldn’t have been able to pay for otherwise.

What are your plans for the Clouds Hill future?

We’re definitely going to open another office in L.A. and we’re still pretty busy in the studio. It certainly won’t be boring.

Thank you, Johann!

Join our Community